Another recurring theme in my recent trip to England with university students was the grandeur of major cathedrals and how they point to the glory of God.

Some personal history: I grew up in the Lutheran church, which has a lot of tradition. The stained-glass windows of the church told stories, and I loved the atmosphere of the stained glass.

Then I left that tradition and became part of the new evangelical and charismatic world that came into prominence in the early 1970s. I was a Jesus Movement guy. I concluded at the time that my church was too tradition-bound and had lost its vitality. To a great extent, I was correct.

Yet I now miss the feelings that go along with the tradition. I remember fondly how the atmosphere made me sense the presence of God. Evangelical churches might want to consider more stained glass.

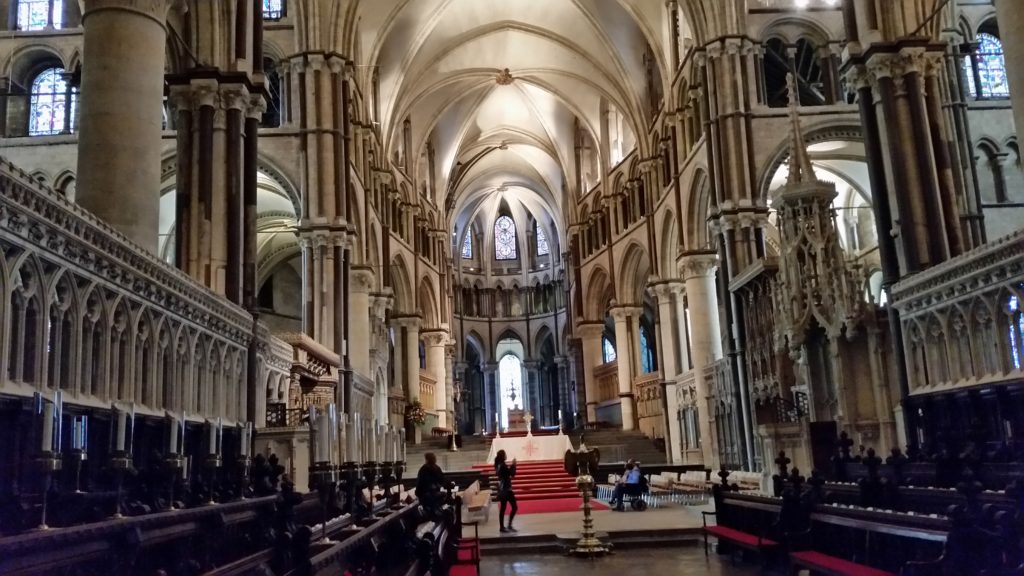

Three of the cathedrals we visited stand out for me. The first is Canterbury.

This is the headquarters for the Church of England. The edifice and the grounds were far more extensive than I expected, and just walking into the cathedral re-created within me the early years of my Lutheran experience.

These medieval cathedrals had a distinct purpose: to point worshipers to the awesomeness of God and to help them meditate on His holiness.

Salisbury Cathedral, which has the tallest spire in England, also was impressive. It had the most unusual baptismal font I’ve ever seen.

The cathedral also incorporated a significant piece of English history, a piece that directly affected America: an original copy of the Magna Carta, on display in its beautiful Cloister House.

Photos of the aging document itself were not permitted, but it was worthwhile just to be face to face with it.

Sunday in London saw us attending the worship service in Westminster Abbey.

I wasn’t quite sure if a service there would be as Christ-centered as I would have liked. The pleasant surprise was how orthodox and Biblical it was. And to have that solid orthodoxy take place in such a magnificent structure was awe-inspiring. I recall telling the student next to me how much I appreciated the architecture because it drew one’s attention upwards and focused both the mind and heart on God’s presence.

As I went forward for communion, it was pointed out to me by another in our group that at the end of our row of chairs was this particular memorial:

Throughout the entire service, I was sitting practically next to the C. S. Lewis memorial without knowing it. For me, that was a special treat. I’ll have more to say about Lewis when I write about our foray into Oxford and to Lewis’s home, the Kilns.

I realize that architecture and grand buildings are not the essence of the Christian faith. Yet I honestly believe we in the evangelical world, in our quest for informality and spontaneity, might be missing a crucial element in the faith. We focus so much on the personal relationship (“Jesus is my co-pilot”) that we sometimes forget the regal nature of our Lord.

I realize that architecture and grand buildings are not the essence of the Christian faith. Yet I honestly believe we in the evangelical world, in our quest for informality and spontaneity, might be missing a crucial element in the faith. We focus so much on the personal relationship (“Jesus is my co-pilot”) that we sometimes forget the regal nature of our Lord.

As I sat in the Westminster service, I was refreshed by the solemnity of the service itself and the atmosphere of the place. I came away encouraged in the Lord.

What we need are more fellowships that can combine the grandeur of traditional worship with the freshness and vitality of the personal relationship with Christ. It’s a combination rarely achieved.