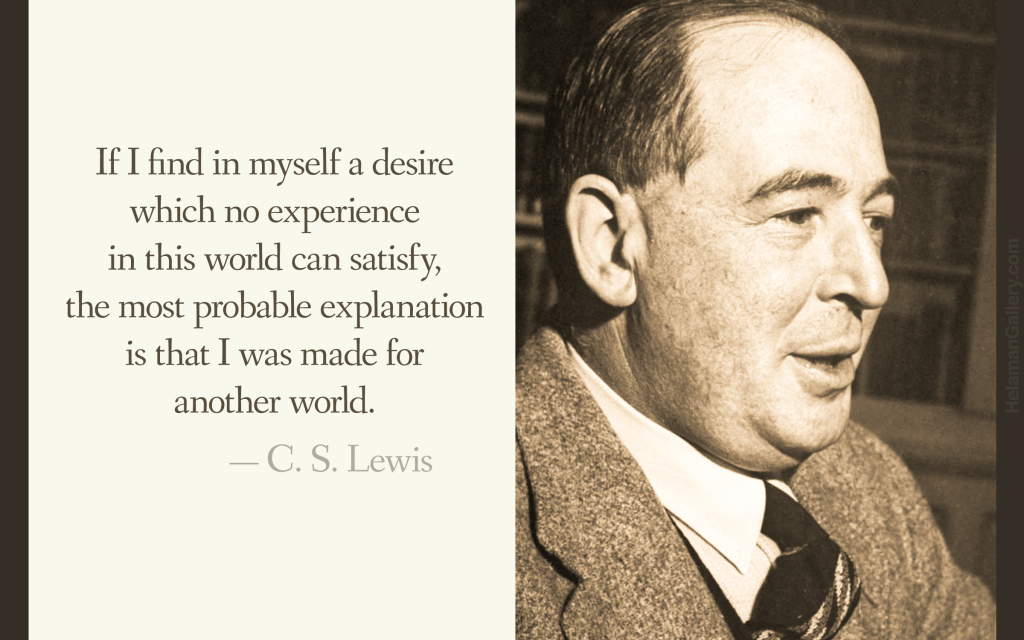

I’ve now completed my research into the letters of C. S. Lewis to Americans. It was a joy to delve into them. Near the end of his life, Lewis wrote often of his expectation of heaven. He was in bad health for the last couple of years, and held rather loosely to this world. As he explained to Mary Van Deusen, one of his most regular correspondents, who was contemplating a move from one house to another,

I think I share, to excess, your feeling about a move. By nature I demand from the arrangements of this world just that permanence which God has expressly refused to give them. It is not merely the nuisance and expense of any big change in one’s way of life that I dread. It is also the psychological uprooting and the feeling: to me, as to you, intensely unwelcome of having ended a chapter. One more portion of oneself slipping away into the past! I would like everything to be immemorial, to have the same old horizons, the same garden, the same smells and sounds, always there, changeless. The old wine is to me always better. That is, I desire the “abiding city” where I well know it is not and ought not to be found. I suppose all these changes shd. prepare us for the far greater change which has drawn nearer even since I began this letter. We must “sit light” not only to life itself but to all its phases. The useless word is “Encore!”

Lewis was not seeking an encore of life in this world; instead, he longed for the next. Nine months after writing that letter, he slipped into a coma from which the doctors thought he would not recover. The Church of England held Last Rites for him and everyone prepared for him to die. Half an hour later, he sat up and asked for some tea.

Two months after that, he wrote to a lifelong friend from Ireland, Arthur Greeves, about that experience:

Tho’ I am by no means unhappy I can’t help feeling it was rather a pity I did revive in July. I mean, having been glided so painlessly up to the Gate it seems hard to have it shut in one’s face and know that the whole process must some day be gone thro’ again, and perhaps far less pleasantly! Poor Lazarus! But God knows best.

Those words reveal a man ready to go at any time—in fact, eager to do so—yet fully submitted to the will of God in the matter. He didn’t have long to wait, and the “going” was quick and painless in the afternoon of November 22, 1963.

While the rest of the world was reeling from the shock of the assassination of an American president, C. S. Lewis received his release from the trials and sorrows of this world and took up residence—permanent residence—in the presence of God.