I’ve been periodically presenting glimpses into American history, and have been writing about the Pilgrims and Puritans for quite some time now. There’s a lot to say. I’ve analyzed the Christian roots of the colonies they started (primarily Plymouth, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, with Rhode Island added in) and have pointed to both the high points and low points of their development.

In the 1680s, those colonies, along with New York, faced a threat to their original goals. The new king, James II, decided that they were not sufficiently under the thumb of the royal government and decreed a change in their charters. He officially revoked all the charters and reorganized the area into one large colony directly under his control. He called it the Dominion of New England.

In the 1680s, those colonies, along with New York, faced a threat to their original goals. The new king, James II, decided that they were not sufficiently under the thumb of the royal government and decreed a change in their charters. He officially revoked all the charters and reorganized the area into one large colony directly under his control. He called it the Dominion of New England.

This meant that, by his command, the Separatist colony of Plymouth would now lose its uniqueness. Massachusetts Bay would no longer be the “city on a hill” that its founders hoped it would be. Connecticut, which gave us our first constitution, would be melded together with the others and lose its own identity and the government it had created. Rhode Island, founded by Roger Williams, and recently granted a new charter, would now have to relinquish it.

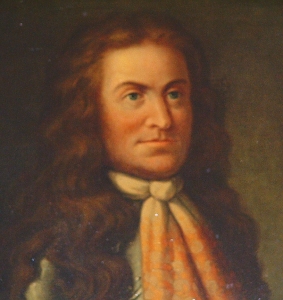

To oversee this change, James appointed as governor Sir Edmund Andros, who was now responsible for administrating the entire area, New York included.

To oversee this change, James appointed as governor Sir Edmund Andros, who was now responsible for administrating the entire area, New York included.

Andros’s charge was to implement a number of changes. First, Anglicanism was now to be promoted, thereby putting an end to both Separatism and deviations within the Church of England that the Puritans had put into effect.

Second, all land titles were to be reexamined. It didn’t matter if you had held title to your land for decades; if the king thought someone else would be better suited to have that land, it could be taken from you. Private property was no longer secure.

Third, town meetings—the political lifeblood of the New England communities–were now to be limited to one per year. The aim, obviously, was to eliminate any political discussions that didn’t go in the direction the king desired.

This new arrangement, though, came to a sudden halt when James, who was a closet Catholic, had married a French Catholic to be his queen, and who was now in the process of raising his son—and heir—as a Catholic, ran afoul of the whole Protestant tenor of the country. What followed is what historians call either the Glorious Revolution or the Bloodless Revolution. It’s as if the entire nation rose up and threw out its king; he had squandered all his political capital.

With James no longer on the throne, the colonies reestablished themselves. The new co-monarchs, William and Mary, did examine all charters. They made some changes to the Massachusetts charter, eliminating the rule that only church members could vote and installing a royal governor. But they allowed both Connecticut and Rhode Island to return to their former status.

An interesting sidelight to this episode is what Connecticut did when faced with the loss of its charter. It refused to turn it over, hiding it, instead, inside an oak tree in Hartford. When the Dominion of New England fell by the wayside, the colony retrieved the charter and picked up where it left off.

The tree became known as the Charter Oak. As you may know, each state has a quarter dedicated to it, and could choose what image it wanted on the back. If you look at the back side of the quarter that features Connecticut, you will see an image of that Charter Oak. It’s a testimony to the desire for self-government that existed in these early settlers.

The tree became known as the Charter Oak. As you may know, each state has a quarter dedicated to it, and could choose what image it wanted on the back. If you look at the back side of the quarter that features Connecticut, you will see an image of that Charter Oak. It’s a testimony to the desire for self-government that existed in these early settlers.

The threat of tyrannical government has reared its head many times in American history. This was the first attempt, and it was soundly defeated, though not by the colonists but by the nation itself back in England. The next time the British crown tried to impose a tyranny, though, the colonists were forced to take matters into their own hands and won their independence.