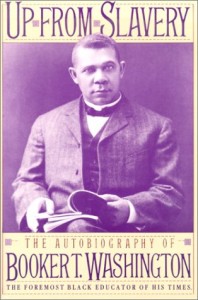

During this Independence Week, I think it highly appropriate to mention I recently finished reading Booker T. Washington’ s fascinating autobiography Up From Slavery. As with the Coolidge biography I noted on Monday, I had given a thumbs-up to Washington’s personal reflections in an earlier blog. Now, having completed reading his thoughts on life and how God wants us to live it, I can enthusiastically endorse it unconditionally.

During this Independence Week, I think it highly appropriate to mention I recently finished reading Booker T. Washington’ s fascinating autobiography Up From Slavery. As with the Coolidge biography I noted on Monday, I had given a thumbs-up to Washington’s personal reflections in an earlier blog. Now, having completed reading his thoughts on life and how God wants us to live it, I can enthusiastically endorse it unconditionally.

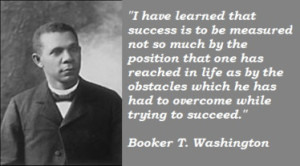

Washington was an impressive man. His devotion to the principle of self-government and his emphasis on character building permeate his philosophy of life. He rejoiced that he and his students at the Tuskegee Institute  had to endure hard times. He noted repeatedly that it is in those hard times when we learn the greatest lessons. Rather than an easy road, he preferred to tackle problems, knowing the struggle itself would make him a better man.

had to endure hard times. He noted repeatedly that it is in those hard times when we learn the greatest lessons. Rather than an easy road, he preferred to tackle problems, knowing the struggle itself would make him a better man.

His Christian faith also comes across clearly. Another historian has commented that Washington was not a devout Christian. One of the reasons I read his autobiography was to get some inkling of whether that assessment was accurate. In his own words, Washington declares,

While a great deal of stress is laid upon the industrial side of the work at Tuskegee, we do not neglect or overlook in any degree the religious and spiritual side. The school is strictly undenominational, but it is thoroughly Christian, and the spiritual training of the students is not neglected. Our preaching service, prayer-meetings, Sunday-school, Christian Endeavour Society, Young Men’s Christian Association, and various missionary organizations, testify to this.

He also had good words to say about his fellow Christians:

In my efforts to get money I have often been surprised at the patience and deep interest of the ministers, who are besieged on every hand and at all hours of the day for help. If no other consideration had convinced me of the value of the Christian life, the Christlike work which the Church of all denominations in America has done during the last thirty-five years for the elevation of the black man would have made me a Christian.

Then there’s the testimony of his attitude toward those who might be considered enemies:

It is now long ago that I . . . resolved that I would permit no man, no matter what his colour might be, to narrow and degrade my soul by making me hate him. With God’s help, I believe that I have completely rid myself of any ill feeling toward the Southern white man for any wrong that he may have inflicted upon my race. . . . I pity from the bottom of my heart any individual who is so unfortunate as to get into the habit of holding race prejudice.

He explained how he was led to conduct himself:

When I first came to Tuskegee, I determined that I would make it my home, that I would take as much pride in the right actions of the people of the town as any white man could do, and that I would, at the same time, deplore the wrong-doing of the people as much as any white man. I determined never to say anything in a public address in the North that I would not be willing to say in the South. I early learned that it is a hard matter to convert an individual by abusing him, and that this is more often accomplished by giving credit for all the praiseworthy actions performed than by calling attention alone to all the evil done.

If you were to read Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, I think you might come to the same conclusion I did: here is a model of a Christian man whose attitude and principles should be emphasized in our society once again. Booker T. Washington is one of the true heroes of American history.