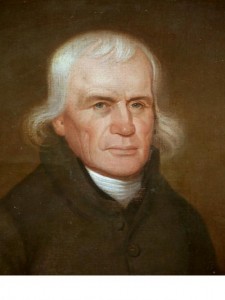

I recently completed reading some of John Wesley’s journal entries and letters. I feel a kinship with him. One of his disciples was Francis Asbury, considered more than anyone else the founder of the American Methodist church, and the namesake for a Christian college in Kentucky. I’ve now begun looking at excerpts from his journal as well. His faith was dynamic, not static. He preached a personal gospel with all its social implications, speaking out against slavery, drinking, gambling, and other practices that degrade a people. But he didn’t just denounce sinful actions; he reached out to anyone who would listen to the message of redemption. He helped educate the illiterate by building schools and colleges, founded Sunday Schools, and preached to those in prison. God placed within him a desire to spread the Word to as many as possible.

I recently completed reading some of John Wesley’s journal entries and letters. I feel a kinship with him. One of his disciples was Francis Asbury, considered more than anyone else the founder of the American Methodist church, and the namesake for a Christian college in Kentucky. I’ve now begun looking at excerpts from his journal as well. His faith was dynamic, not static. He preached a personal gospel with all its social implications, speaking out against slavery, drinking, gambling, and other practices that degrade a people. But he didn’t just denounce sinful actions; he reached out to anyone who would listen to the message of redemption. He helped educate the illiterate by building schools and colleges, founded Sunday Schools, and preached to those in prison. God placed within him a desire to spread the Word to as many as possible.

As a result, he went up and down the land for 45 years, mostly on horseback, winning converts and emphasizing that his purpose was to “reform the continent and spread scriptural holiness.” He was the inspiration for the famous Methodist circuit riders who made sure the gospel could be heard in even the remotest locations. When he died, he left churches and the impress of his personality from Ontario to Georgia, from Virginia to Ohio, and upon all the states within that circuit.

His journal entries reveal a man driven to be all he could be for God. At age 26 he left his native England for the New World and never returned to the Old. Shortly after arriving, one entry declared his goal: “I have nothing to seek but the glory of God; nothing to fear but his displeasure.” He studied the Bible constantly and sought to speak with the authority of Scripture, yet never lost sight of his dependence on the Spirit. He put it this way:

It seems strange, that sometimes, after much premeditation and devotion, I cannot express my thoughts with readiness and perspicuity; whereas at other times, proper sentences of Scripture and apt expressions occur without care or much thought. Surely this is of the Lord, to convince us that it is not by power or might, but by his Spirit the work must be done. Nevertheless, it is doubtless our duty to give ourselves to prayer and meditation, at the same time depending entirely on the grace of God, as if we had made no preparation.

Asbury also kept a close watch on his heart, wanting to ensure that he never grew cold in his faith:

My mind has been much perplexed about wandering thoughts in prayer, though Mr. Wesley’s deep and judicious discourse on that subject has afforded me no small satisfaction. He hath both shown the causes of those thoughts, which are not sinful, and incontestably proves that they contract no guilt. Yet a devout and tender mind must be grieved to find any kind of temptation in that sublime exercise wherein the whole soul desires to be employed.

As a historian, I’m naturally interested in accounts of men like Asbury; as a Christian, I’m drawn to his thoughts and his heart. The two merge nicely. Further, I want and need to be challenged with respect to my own walk. Do I seek nothing but God’s glory? Am I studying His Word sufficiently yet simultaneously dependent on His Spirit to lead me? Will my heart and mind stay tender toward the One who gave me a second chance in life?

Thank you, Francis Asbury, for making me think on these things.