“God created things which had free will. That means creatures which can go either wrong or right,” C.S. Lewis states in “The Shocking Alternative” chapter of Mere Christianity. He continues, “Some people think they can imagine a creature which was free but had no possibility of going wrong; I cannot. If a thing is free to be good it is also free to be bad.” This, of course, leads to the question of why God made such a choice in creating human beings. If evil can result from giving mankind free will, was that wise? Lewis’s answer?

Why, then, did God give them free will? Because free will though it makes evil possible, is also the only thing that makes possible any love or goodness or joy worth having.

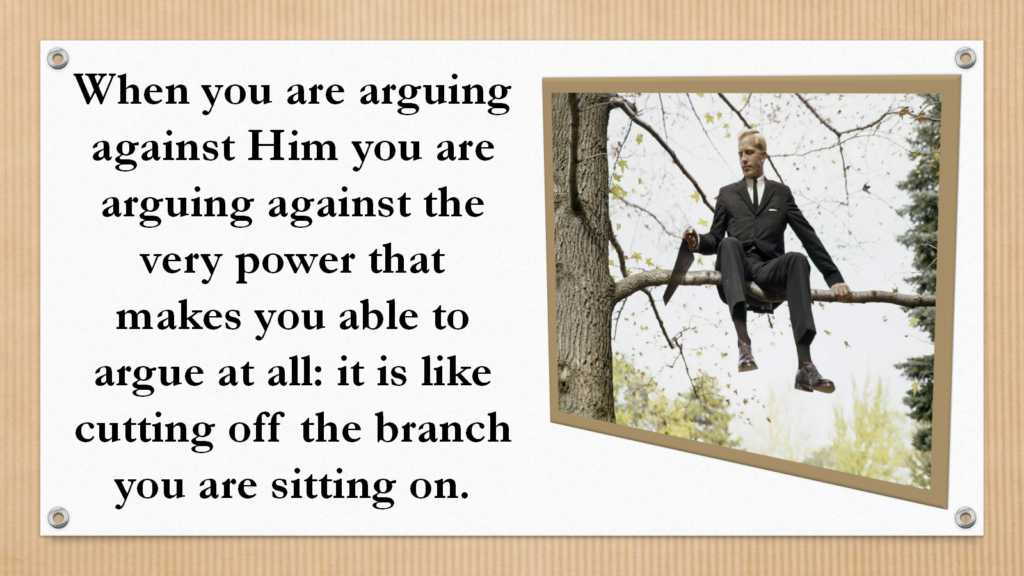

Mankind has always tried to argue with God’s ways. As Lewis notes in another essay, in the modern world, we tend to put God on trial for His actions rather than the other way around. As if we are wiser and—absurd as it sounds—more moral, more just, than the Creator of the universe. Lewis acknowledges that people will become God’s accusers. But he is pretty direct in response when he asserts,

But there is a difficulty about disagreeing with God. He is the source from which all your reasoning power comes: you could not be right and He wrong any more than a stream can rise higher than its own source.

Continuing the logic, Lewis adds this:

The bottom line here is that when the Lord brought this earth into existence and peopled it, His goal was to create the kind of beings who could truly, genuinely, sincerely love Him and one another. If they were merely puppets and/or marionettes on strings, there would be nothing valuable in that at all. Yes, by endowing mankind with free will, God was taking a risk. If we read the backstory of heaven and the fall of Satan correctly, the possibility of good and evil was present prior to man’s creation—and some angelic beings fell into rebellion due to their own free will.

So when God placed mankind on this planet, the risk was real. As Lewis says, “The moment you have a self at all, there is a possibility of putting Yourself first—wanting to be the centre—wanting to be God, in fact. That was the sin of Satan: and that was the sin he taught the human race.”

Each of us like sheep has gone astray, seeking to set ourselves up as the final word in our lives. That is the essence of sin. And the reason it never works well is that we have gone against the grain, so to speak. We are not operating in the manner that God intended. “He Himself is the fuel our spirits were designed to burn, or the food our spirits were designed to feed on. There is no other,” Lewis informs us. “That is why it is just no good asking God to make us happy in our own way without bothering about religion.”

I don’t like all the sin in the world; neither does God. But I also know that real righteousness is not possible without this divine gift of free will. I rejoice that He has provided it. Only in that way am I able to freely respond to His love and mercy. Only via free will can life have any meaning. Those who believe the opposite are not wiser than God.

Here’s the irony, of course. Some argue against free will, but it’s the very free will that they possess that gives them the freedom to argue. They are attempting to cut off the very branch on which they sit.