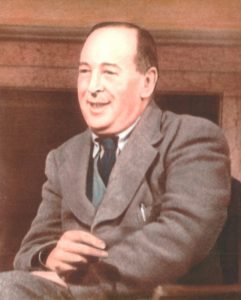

“No Christian and, indeed, no historian could accept the epigram which defines religion as ‘what a man does with his solitude,” began C. S. Lewis in his “Membership” essay. “It was one of the Wesleys, I think, who said that the New Testament knows nothing of solitary religion.”

“No Christian and, indeed, no historian could accept the epigram which defines religion as ‘what a man does with his solitude,” began C. S. Lewis in his “Membership” essay. “It was one of the Wesleys, I think, who said that the New Testament knows nothing of solitary religion.”

Why is that? “The Church is the Bride of Christ. We are members of one another.”

Lewis continues by pointing out that modern society tries its best to confine religious beliefs and practices to the private life, and what he said in this essay decades ago is even more true today. He then notes the paradoxical nature of the “exaltation of the individual in the religious field . . . when collectivism is ruthlessly defeating the individual in every other field.”

The society of Lewis’s day, as he describes it, tried to denigrate any time for the individual as it pushed the idea of collectivism.

There is a crowd of busybodies, self-appointed masters of ceremonies, whose life is devoted to destroying solitude wherever solitude exists. . . .

If a really good home . . . existed today, it would be denounced as bourgeois and every engine of destruction would be levelled against it. And even where the planners fail and someone is left physically by himself, the wireless has seen to it that he will be . . . never less alone when alone.

We live, in fact, in a world starved for solitude, silence, and privacy, and therefore starved for meditation and true friendship.

One wonders how much more Lewis would emphasize this if he were to witness what takes place in our day with the barrage of entertainment and social media drowning out genuine solitude and friendship. We think we are reclaiming both through social media platforms, but we may be fooling ourselves.

Both in Lewis’s day and in ours, the world “says to us aloud, ‘You may be religious when you are alone,'” yet “it adds under its breath, ‘and I will see to it that you never are alone.'”

Make Christianity a private affair and then banish all privacy is how Lewis explains that approach. Christians then fall into the trap of reacting against this “by simply transporting into our spiritual life that same collectivism which has already conquered our secular life.” He calls that “the enemy’s other stratagem.” Here’s what he means:

Like a good chess player, he is always trying to manoeuvre you into a position where you can save your castle only by losing your bishop.

In order to avoid the trap we must insist that though the private conception of Christianity is an error, it is a profoundly natural one and is clumsily attempting to guard a great truth.

Behind it is the obvious feeling that our modern collectivism is an outrage upon human nature and that from this, as from all other evils, God will be our shield and buckler.

So, we have a tendency to accept an error (collectivism) in our attempt to reject the privatization of our faith.

Collectivism is found primarily in politics. Lewis goes on to make this statement, one that I find quite appropriate to our current societal state:

A sick society must think much about politics, as a sick man must think much about his digestion; to ignore the subject may be fatal cowardice for the one as for the other. But if either comes to regard it as the natural food of the mind—if either forgets that we think of such things only in order to be able to think of something else—then what was undertaken for the sake of health has become itself a new and deadly disease.

We are a society immersed in politics. For many, it is the be-all and end-all of life. Any society in that state remains sick.

Christian faith should be our focus, not politics. Yet this faith cannot be either a private thing or a copy of secular collectivism. We lose if we go in either of those two directions. The true Body of Christ as explained in Scripture is of another nature entirely.

What is that nature? I’ll deal with that as I conclude Lewis’s thoughts in this essay in a future post.