Clyde Kilby, the man largely responsible for the largest C. S. Lewis repository in America—the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College—wrote an article in December 1953 detailing his personal meeting with Lewis at Oxford.

Before he got to Lewis’s rooms, he wrote, someone led him astray about the nature of the man he was going to meet. Kilby’s wife was accompanying him, and he asked at the college gate “whether there was anything to the report that Mr. Lewis disliked women.” Whoever he spoke with made it seem that there was some truth in the report, so his wife went shopping instead, and he met Lewis by himself.

Rumors of Lewis being antagonistic toward, disdainful of, and/or frightened by women have been bandied about for years. How those rumors got started, why there is no truth behind them, and how Lewis actually did view women and the way he treated them is the subject of a fairly new book that I can heartily recommend.

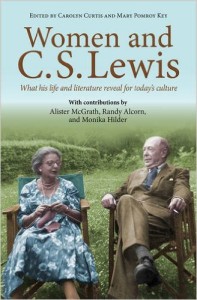

When I attended the C. S. Lewis Foundation fall retreat, Women and C. S. Lewis was a gift for each attendee. It is comprised of short essays by a variety of people, both men and women, well known within the current Lewis academic world.

When I attended the C. S. Lewis Foundation fall retreat, Women and C. S. Lewis was a gift for each attendee. It is comprised of short essays by a variety of people, both men and women, well known within the current Lewis academic world.

Edited ably by Carolyn Curtis and Mary Pomroy Key, this volume deals systematically with all pertinent questions about Lewis’s relationships with women.

The first section covers the women who crossed paths with him personally, beginning with his mother who died of cancer when he was just nine years old. Then there is a treatment of the somewhat fuzzy relationship with Mrs. Moore, whom he called his mother for the rest of her life. Joy Davidman naturally is included since she had the greatest impact on his final decade as his wife. His interactions with writer Dorothy Sayers and poet Ruth Pitter are also examined.

Section two then delves into how Lewis depicts women in his novels: Lucy and others in the Narnia series; the Green Lady of Perelandra and Jane Studdock inThat Hideous Strength; the highly acclaimed (in heaven, at least) Sarah Smith of The Great Divorce; the positive portrayals in The Pilgrim’s Regress; and of course his fascinating approach toTill We Have Faces, where he writes the entire novel from a woman’s perspective.

A shorter section looks at his poetry and how women are treated (favorably) and section four highlights how Lewis has influenced our current generation’s discussion about the role of women in society and church. Finally, there are essays on how Lewis’s views on women impacted some who speak out publicly today on the issue.

One cannot read this book without dismissing the old canard that Lewis had a problem with women. The arrival of this volume is both timely and welcome. Get it. You will enjoy it.