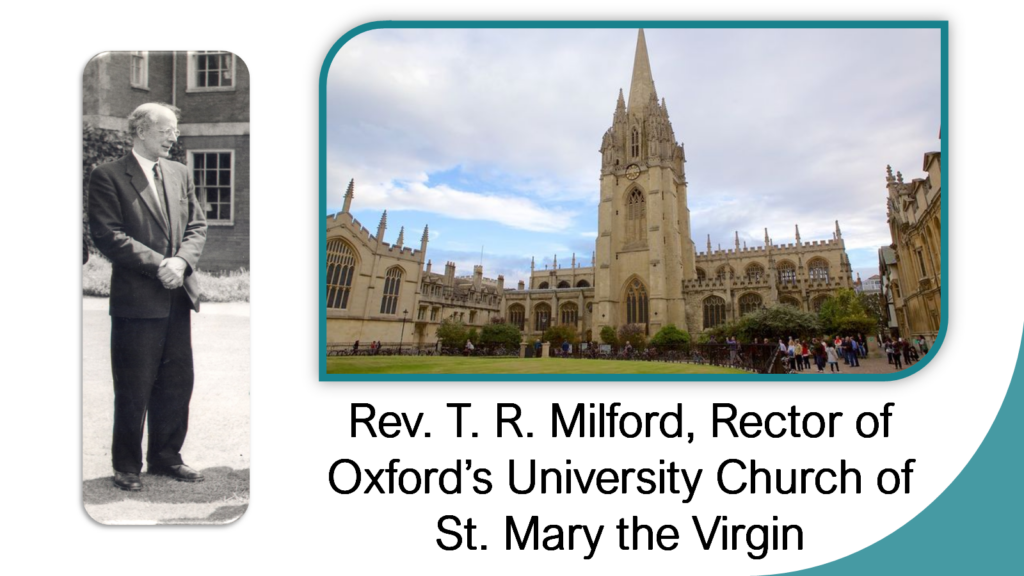

Rev. T. R. Milford, rector of Oxford’s University Church of St. Mary the Virgin, wanted an authority to speak on the importance of continued education in a national crisis. That crisis was the Second World War, which Britain entered in September 1939 after the Nazi invasion of Poland.

Why was this topic on the rector’s mind? Some would undoubtedly question—and perhaps some already were questioning—why a university such as Oxford should continue to prioritize academics at a time when all the energies of the nation needed to be focused on the war effort. Rev. Milford did not have far to look to find his authority, sending his invitation to Oxford don C. S. Lewis, who was beginning to make his reputation as a noted scholar and a writer on Christian themes.

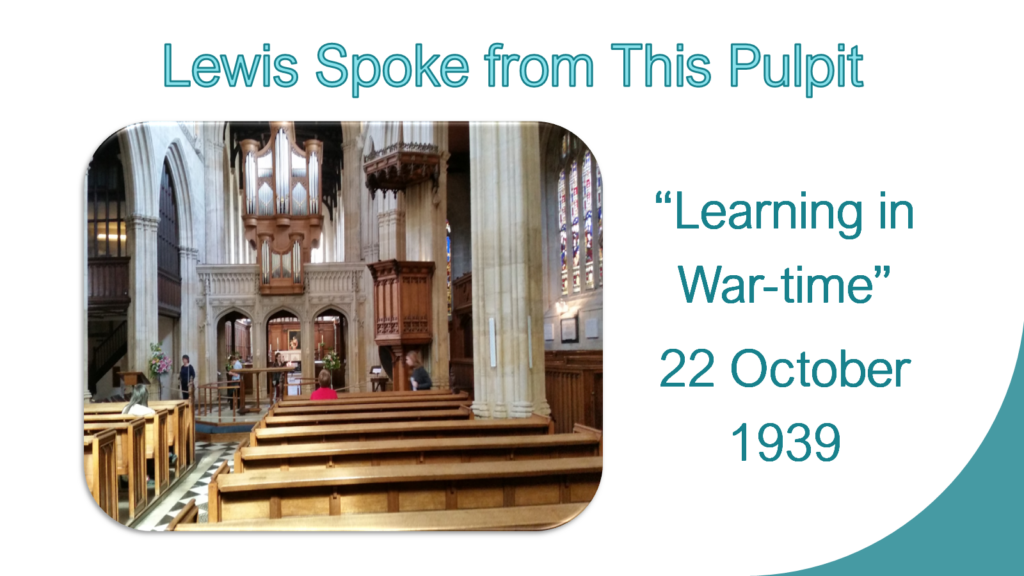

Thus, Lewis mounted the pulpit on 22 October 1939 to give a sermon, an argument, a rationale, an apologetic—all those words apply—for the significance of learning/education even at a time when all of Europe was aflame with war. Lewis was no clergyman and not a trained theologian, so it was quite the mark of respect for the rector to have asked him to deliver such an important message. It also was a great responsibility to make the case effectively.

What was his case? Lewis begins by acknowledging that it might seem odd to be concerned about a university education when a great war is beginning. Why be interested in academic pursuits when lives and liberties are at stake? If Rome is burning, why waste time fiddling? And is it right for Christians, who think seriously about the reality of Heaven and Hell, to devote valuable time to what might be considered trivialities compared to eternal matters? He does a fine job of asking the right questions. He then offers the perspective that a war doesn’t change anything essentially; it merely makes our situation harder to ignore.

This bold statement of fact about history forms the cornerstone for the rest of his sermon. Christians can pursue knowledge and beauty confidently, he contends, because by doing so they get a deeper understanding of God and might be able to help others do the same. Education, therefore, even in a time of war, can draw people closer to eternal realities. It is at this point in the talk where Lewis emphasizes the role of history in this quest. He says, “Most of all, perhaps, we need intimate knowledge of the past.” Why? We need to be reminded that people in different eras had different assumptions than the people of 1930s-1940s Britain, who are, to a great extent, historically ignorant, he believes.

Lewis continues, “A man who has lived in many places is not likely to be deceived by the local errors of his native village; the scholar has lived in many times and is therefore in some degree immune from the great cataract of nonsense that pours from the press and the microphone of his own age.”

When Lewis used the terms “many times” and “many places,” they sparked the title for my latest book in which I try to explain why knowledge of history is so necessary.

The duty of the educated is to help keep the current age from following after nonsense. That requires a solid knowledge of history and the ability to discern between what is true throughout the ages and what is merely a temporary fashion of one’s own age. This passage in Lewis’s sermon/essay has always stood out to me for two reasons: first, I am an academic, so anything that emphasizes the importance of learning will always attract my attention; second, I am a historian, and I’m constantly concerned over the lack of historical knowledge in our society—a lack that leads us often into repeating the errors of earlier ages.

The significance of historical knowledge emerges once again near the end of Lewis’s sermon when he appeals to the great Christians of the past who had a clear view of death, who even saw it as one of God’s blessings because it reminds us of our own mortality. Drawing upon that ancient knowledge, we see our universe more clearly. We also come to the realization that there are limits to what can be achieved by humanity. It is foolish, he says, to have unrealistic/ un-Christian hopes about human culture. We are not going to achieve heaven on this earth, and if we think this temporary pilgrimage in the world in which we live is ever going to satisfy man’s soul, “we are disillusioned, and not a moment too soon.”

In my attempt to educate the current generation, students in my Lewis course this semester just read “Learning in War-time.” They turned in reports of their observations from reading this essay, then we discussed it in class. They seem to have gleaned much from the experience. What did I get from it? A deep satisfaction that these truths that Lewis offers continue to make students think about eternal realities in light of our temporary pilgrimage on this earth.