I’ve written previously about C. S. Lewis’s appreciation of Dorothy L. Sayers’s works. He was particularly enthused by her new translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. When he first learned she was undertaking that task, he remarked in a letter to her, “I expect I shall find you loud pedaling the comic element more than I approve, but it is much better to have your Dante as your Dante than to have a compromise between it and some one else’s. That’s the only way a translation can be really alive.”

Upon reading the Inferno/Hell translation, he called it “a stunning work.” Intending to pay attention to the translation aspect, he found himself instead with a different focus: “Before I’ve read a page I’ve forgotten all about you and am thinking only of Dante, and two pages later I’ve forgotten about Dante and am thinking only about Hell. Brava, bravissima.“

Sayers wrote back that even though she had received many nice letters about Inferno, that she considered his the nicest. Why? “Because you understood so well what the thing’s all about, and what a translation aims at, and why it is bound to be one thing or the other and can’t very well be two incompatible things at once.”

When Sayers completed Purgatorio, Lewis’s praise reached a new level: “I am really delighted with it. Your Inferno was good, but this is even better. I had wondered how the muscular, often rough & colloquial, manner which you need for Hell would serve you on the Mountain! Innocent and faithless that I was—and of course all the time you knew that it wouldn’t do and had new modulations in store. By gum, it makes one hungry for your Paradiso.”

Of course, while Sayers did move forward with Paradiso, she died before finishing it. Fortunately, her friend Barbara Reynolds was able to complete the last third; most of the translation remains Sayers’s.

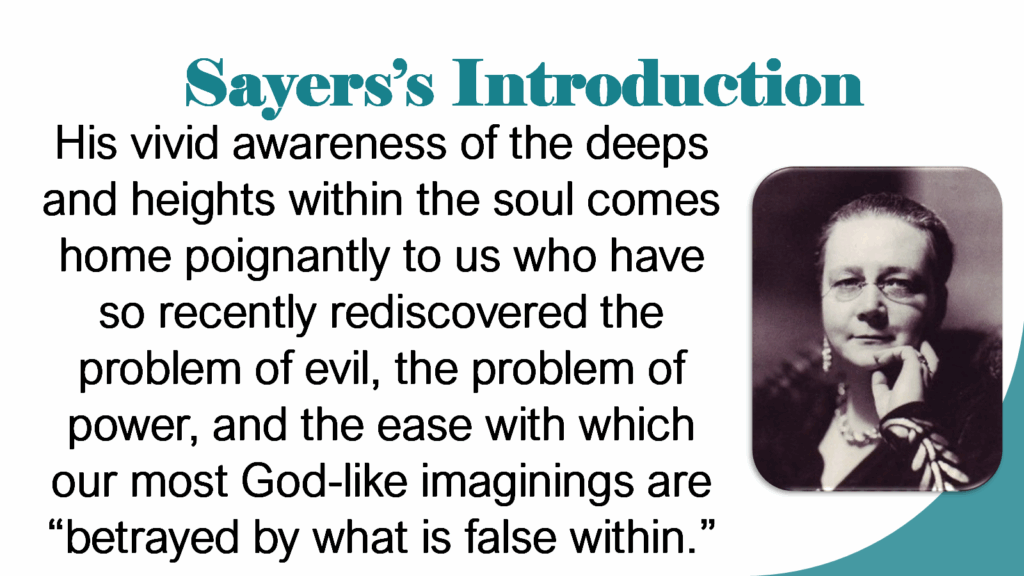

I had never ventured into Dante’s Divine Comedy, wondering if it would be too boring or too hard to understand. But since I had loved Sayers’s other works, I decided a few years ago to take the plunge. I’m glad I did. What struck me from the start was her introduction to Dante. It gave me a perspective I didn’t have—and her wording, as in her other works—hit home to me.

Her comment about being so recently rediscovering the problem of evil was a reference to Hitler and the depravity of his rule, culminating in a world war. She warns of being betrayed by what is false within, thereby putting readers on notice that they should set aside any “God-like imaginings” that might be stirring within them. Humility is what we need.

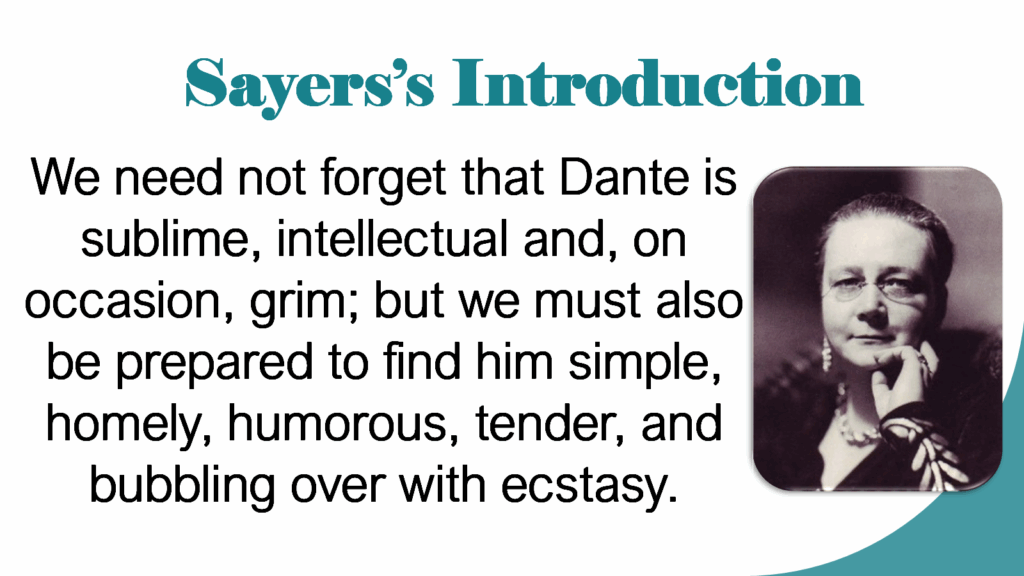

Sayers then takes to task those who attempt to portray Dante as a “peevish political exile” who delighted in “putting his enemies in Hell and his friends in Paradise.” She corrects that assessment:

Sayers then makes an application from her decidedly foundational Christian worldview with respect to the nature of man:

Lewis wrote his “panegyric” for Sayers that was read at her funeral, Lewis himself being too ill at the time to attend. In it, he praised all of her important works, but ended with comments on the Dante translation. “No version can give the whole of Dante. So at least I said when I read her Inferno. But, then, when I came to the Purgatorio, a little miracle seemed to be happening. She had risen, just as Dante himself rose in his second part: growing richer, more liquid, more elevated.” He continued, “Then first I began to have great hopes of her Paradiso. Would she go on rising? Was it possible? Dared we hope?” He concluded with these poignant words.

Well. She died instead; went, as one may in all humility hope, to learn more of Heaven than even the Paradiso could tell her. For all she did and was, for delight and instruction, for her militant loyalty as a friend, for courage and honesty, let us thank the Author who invented her.

I love those final words: “Let us thank the Author who invented her.” I couldn’t agree more.