Reading the letters of famous people gives researchers like me greater insight into how their minds work. What’s even better is to find letters between superb thinkers and writers that illuminate how they think and what is going on inside them.

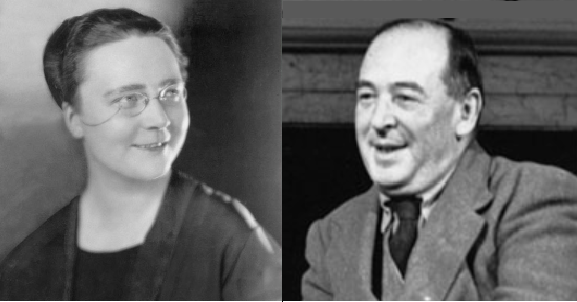

A great example of this are the letters between C. S. Lewis and Dorothy L. Sayers. They are lively and fascinating.

When Lewis and Sayers corresponded in 1946 about the value of one’s labors—in this case, their writing endeavors—Lewis opened up to Sayers about one of his concerns. In fact, he called it a “frequent uneasiness” that crept into his defense of the Christian faith. He put it this way: “Apologetic work is so dangerous to one’s own faith. A doctrine never seems dimmer to me than when I have just successfully defended it.”

Sayers responded within a week with words that sought to help Lewis grasp why he might feel that way and to offer her own insight into an overall picture of such a feeling, removing it from the narrow concern over apologetics and giving it a broader scope.

She begins by branding that feeling as “a nemesis that attends all art & all argument.” Lewis, she suggests, needs to expand his scope of vision in this regard. “It is dimmer (& in one sense always will be) because you have put something of yourself into it.” She continues with an analogy: “You can’t completely remove the alloy from the gold. This being a fallen world, the incarnate image never perfectly reflects the idea; you will never again be able to see the thing quite without the contributed distortion.” Again, the application goes beyond apologetics: “But it would be exactly the same if you were writing about Shakespeare or a piece of landscape. . . . But that is the price of doing or saying anything–& time, & the critical judgment, will enable you to distinguish the strands, so far as they can be distinguished.”

Sayers, a playwright of renown as well as writer of hugely successful detection novels, uses her specialty to augment her argument:

You have been obliged to lend imaginative sympathy to the arguments on the other side. Well, so you have; & in play-writing this is the biggest asset of all, because it enables you to make the “bad” characters real people, & not mere Aunt Sallies. And there, you experience & make use of, the full value of the thing which is not pure dialectic. But in dialectic, you more or less deprive yourself of the power of that important factor, & so begin to feel that you are being ingenious rather than candid. But, once out of the heat of the conflict, you set the right balance back—unless, of course, your arguments really have been unsound, in which case it is just as well to know it.

Sayers then turns to what she hopes is some practical advice for how to deal with the feeling. “You are tired. Having united yourself with the doctrine—you hope fruitfully—you are worried by its plaintive cry: ‘But do you still love me?’ Reassure it courteously & go to sleep.”

Her final comment is along the same line:

I think any professional writer would tell you the same. The first reaction to anything you have just finished is exhaustion & disgust, which transfers itself from the work to the whole subject. (It is in this mood that one passes the worst flagrant errors in proof, because one can hardly bear to look at the thing). The cure is time, change, & a resolution not to return to one’s vomit. Let be.

This is simply one example in this correspondence that lasted until Sayers’s death in 1957. If, as the proverb says, “as iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another,” that is what took place here. A gem uncovered.