My previous post revealed how C.S. Lewis and Dorothy L. Sayers established a relationship as authorial colleagues and friends. Interestingly, Lewis had never read Sayers when she was primarily focused on her Lord Peter Wimsey novels.

In fact, Lewis only read one of the Wimsey tales after being impressed with her Christian writing. As he wrote to his friend Arthur Greeves, “Dorothy Sayers The Mind of the Maker I thought good on the whole: good enough to induce me to try one of her novels–Gaudy Night–wh. I didn’t like at all.” His explanation? “But then, as you know, detective stories aren’t my taste, so that proves nothing.”

As noted in his letter, it was The Mind of the Maker that first got his attention to Sayers’s potential as a scholarly colleague.

He reviewed the book in the journal Theology and noted the thesis of the work, saying,

The purpose of this book is to throw light on the doctrine of the Blessed Trinity and on the process whereby a work of art (specially of literature) is produced, by drawing an analogy between the two.

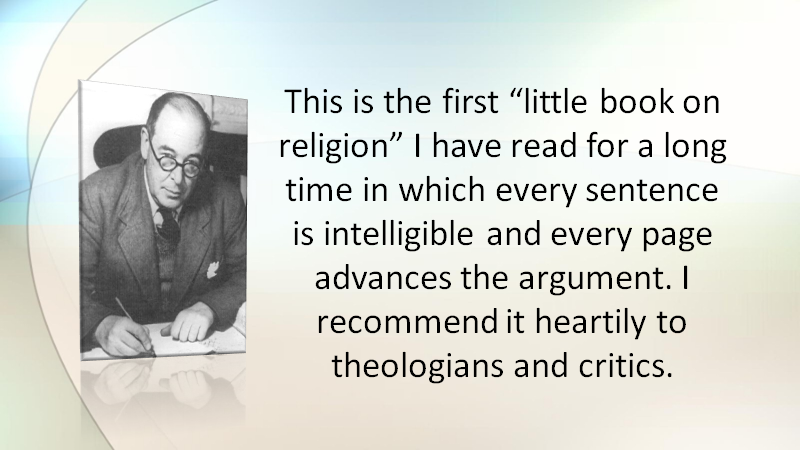

When one reads the review, one finds that his main critique is merely that she might be giving too much encouragement to artists who see themselves in a too highly exalted light. Idolatry must be avoided. Yet he states in the final paragraph the following:

Lewis’s appreciation for Sayers grew considerably when she entered into the field of radio plays during WWII. Her contribution was a series based on the life of Jesus.

Her approach raised considerable controversy because she refused to use King James English, opting instead for contemporary 20th-century English that used common terms and different dialects, and even what some critics called American slang. Another objection was that a law still existed that forbade portrayal of any person of the Trinity in a production. Sayers weathered this storm, stood by her portrayal, and the plays were tremendously successful, even more so because of the interest in the controversy.

Lewis was so impressed with them that when the plays were published in book form, he wrote to Sayers, affirming her work in glowing terms.

Writing to correspondents, Lewis praised The Man Born to Be King as a production that “has edified us in this country more than anything for a long time.” He considered it “excellent, indeed most moving. The objections to it seem to me silly.”

Sayers devoted the final decade of her life to her own translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, which was already one of Lewis’s favorite pieces of literature. When she completed the first part, the Inferno, Lewis was fulsome in his praise, as he wrote to her,

Sayers responded with gratitude for Lewis’s praise.

Part two, the Purgatorio, exceeded Lewis’s expectations:

Sayers completed approximately two-thirds of the Paradiso before death ended her labors. A friend and colleague, Barbara Reynolds, finished the work to ensure that Sayers’s labors were rewarded.

Although Lewis was ill and couldn’t attend her funeral, he wrote his “panegyric” for her in which he regaled her work and her person. I can think of no better way to end this post than by allowing Lewis’s words to be the final words.