I’m a voracious reader and always have been. As a boy, I would come back from the local library with a stack of books in my bike’s basket—and would repeat the exercise regularly. My early adult life was filled with every new Christian book that hit the market. When I later decided to earn a doctorate in history, I devoured every book on American history that came across my path (along with the required texts for courses). And as a devotee of government and public policy, I coupled those types of books with my history selections. In that sense, I was well read.

Yet when it came to what we might term “the classics,” my experience was rather inadequate. I vaguely recall reading a few in my middle- and high-school years: Huckleberry Finn, The Scarlet Letter, Silas Marner, Brave New World, Great Expectations. If there were others, I have forgotten. Anything ancient or prior to the nineteenth century was not on my radar. It’s only been in the past few years that I’ve attempted to make up for this omission.

Interestingly, my desire to “catch up,” so to speak, coincides with my new focus on C. S. Lewis. One can’t read Lewis without being thrust into that other world of writings—whether ancient, medieval, or the later ones that influenced Lewis directly—without developing a thirst for them oneself. After all, how can one be a Lewis scholar without knowing what he read and being conversant with those same texts?

I began with some of those ancients, primarily Plato and Aristotle, and then started to include works such as Thomas More’s Utopia and more Shakespeare: Hamlet, The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice. Next on my Shakespeare list are Macbeth and Othello. I also worked my way through Paradise Lost, which I considered a prerequisite for tackling Lewis’s preface to the tome (I recently finished his Preface to Paradise Lost and found it quite readable).

Lewis’s fondness for G. K. Chesterton led me to Orthodoxy, The Everlasting Man, and The Man Who Was Thursday. His friendship with Dorothy L. Sayers provided the impetus to read her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (I’m only two-thirds of the way through that one) along with most of her own published works, both detective (Peter Wimsey, anyone?) and theological: The Mind of the Maker, The Man Born to Be King, and her marvelous essays on the Christian faith. And of course I had to read George MacDonald’s children’s stories; I already had read his Phantastes and Lilith. Lewis’s friend, Charles Williams, was a must, so I worked my way through five of his novels (four were worthwhile, but one was too occult-oriented for me).

I’ve always loved movie versions of famous books, but have rarely read the books themselves. So I began that quest as well. Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey came first. I recently finished Jane Eyre and Little Women and was impressed by both. I enjoyed Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables very much. My current read is Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop and waiting in the wings is Wuthering Heights.

Yet I don’t want to confine myself to the older books; even though Lewis was fond of the older books, he did say it was important to keep reading new ones. Since I am involved with a local little Inklings group, I’ve picked up on what members of that group have read or are reading. That’s added to my reading regimen also.

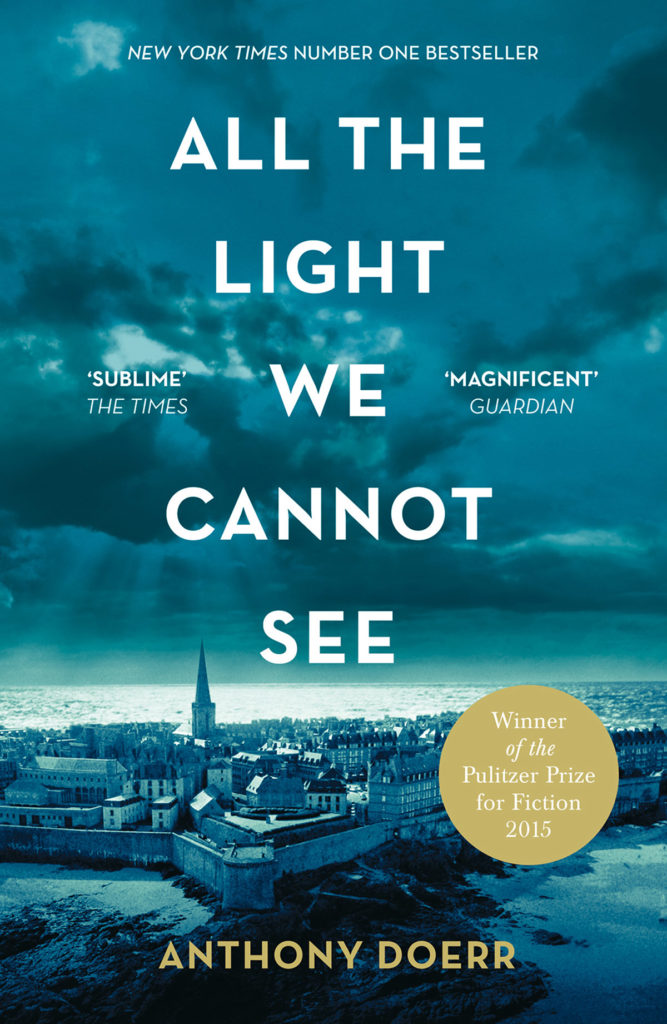

Watership Down by Richard Adams was fascinating, and I’ve become a fan of Khaled Hosseini after reading The Kite Runner and A Thousand Splendid Suns. Three movies led me to the books upon which they were based: The Book Thief, Snow Falling on Cedars, and The Light Between Oceans. I’ll also give a nod here to The Princess Bride after watching that movie countless times and, like others, having memorized certain phrases from it. Yet the one new book that gripped me most has been Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See. This novel that traces the story of a blind French girl surviving WWII and a German boy drafted into the army, and how their lives briefly, but significantly intersected, is at the top of my list. I highly recommend it.

Why did I wait so long to expand my reading? Well, I did have to focus on history and politics because that has been my teaching expertise, and I’m not unhappy for having done so. Yet I am now at a place in my life where I want to take in as much as I can, to broaden my horizon. I now understand better what Lewis meant as he closed his book, An Experiment in Criticism, with these words:

Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realise the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors. We realise it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be himself only, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others. …

In reading great literature I become a thousand men and yet remain myself. Like the night sky in the Greek poem, I see with a myriad eyes, but it is still I who see. Here, as in worship, in love, in moral action, and in knowing, I transcend myself; and am never more myself than when I do.