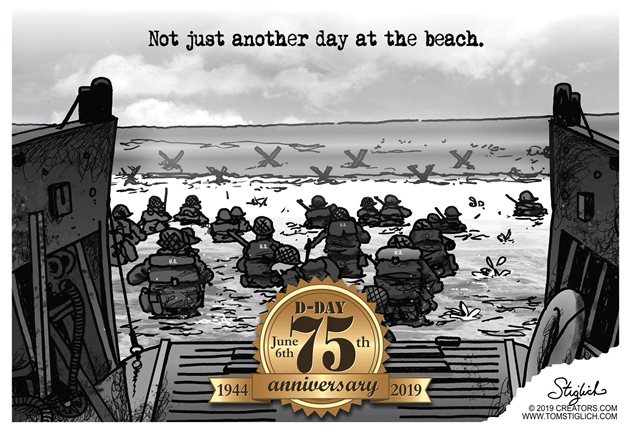

June 6–the 75th anniversary of Operation Overlord, better known as D-Day–the beginning of the liberation of Europe from the Nazis. I do my best in my American history survey course to impress on the students the sacrifices made that day. The current generation has so little sense of history and the impact it still makes on us now. My duty as a professor is to help them see that connection. They have freedom, but it has been bought at a high price.

Americans have always tried to conduct a war with some semblance of civility. That may sound strange, but it’s true. There used to be rules for how war was to be conducted, and those who strayed from those rules received a just punishment, such as the Nazi leaders in the Nuremberg Trials after WWII. Yet war is war, and sometimes the rules of civil society are not the same. If we were to use them in a war, we might not like the result.

One way I attempt to bring home to students the sacrifices of that day is to give them this book by historian Douglas Brinkley, The Boys of Pointe du Hoc: Ronald Reagan, D-Day, and the U.S. Army 2nd Ranger Battalion. It details the training of that special group of soldiers who saw their first action on D-Day. Their task was to take out the massive Nazi guns at the top of that cliff. Their efforts were truly heroic as they succeeded—but at a steep price. The casualty rate for that unit was 90% dead or wounded. I want students to realize what another generation did to ensure that tyranny did not win the day.

The second half of the book describes how President Reagan honored those brave Rangers at the 40th anniversary of D-Day. Standing at the top of Pointe du Hoc in front of the monument to the Rangers, Reagan told the audience of their sacrifices. Some in that audience, though, didn’t have to be told: they were the surviving Rangers who came back for that 40th anniversary. Reagan was part of that generation and served in the army also, though not in a war zone. He wanted to, but his eyesight precluded him from combat. As a result, he always felt a connection to those who were allowed to serve in the way he could not. It was a special moment for both him and those surviving Rangers on that day in 1984.

Fittingly, on the weekend of the 60th anniversary of D-Day, Ronald Reagan went home to be with his Lord. I recall that weekend clearly, as we noted both the anniversary and the president who made sure that D-Day would always be remembered in the proper spirit.

As we commemorate this special day on the 75th anniversary, may we never forget.