Yesterday, November 19, was the 154th anniversary of the Gettysburg Address, one of the most significant and poignant speeches in American history—and also one of the shortest.

The battle at Gettysburg had occurred in July of 1863, three days of some of the most awful warfare the nation has ever endured. It was particularly awful because those who died were all Americans, fighting one another. It took from July to November to clean up the battlefield of all the dead. The carnage practically defied description.

Abraham Lincoln went to Gettysburg to commemorate the victory by Union forces. He wasn’t even advertised as the primary speaker that day—the renowned orator Edward Everett had top billing. Yet no one recalls Everett’s words now. Lincoln’s concise two-minute address has come down to us as one of the most eloquent ever delivered. It doesn’t take long to read, so I offer it to you here:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.

We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

The photographer at the event figured he had time to make the changes necessary to the camera and still catch images of Lincoln’s speech, but he wasn’t prepared for one that short. The only photograph we have of that special occasion is one of Lincoln sitting down right after delivering his comments.

The photographer at the event figured he had time to make the changes necessary to the camera and still catch images of Lincoln’s speech, but he wasn’t prepared for one that short. The only photograph we have of that special occasion is one of Lincoln sitting down right after delivering his comments.

Lincoln’s only error in the speech was in saying that the world would not remember what was said there. At the time, newspapers mocked the president’s address, calling it embarrassing. Speakers were supposed to go on forever, thrilling their audiences with decorative flourishes of oratory. Lincoln instead opted for directness, simplicity, and heartfelt gratitude for those who died.

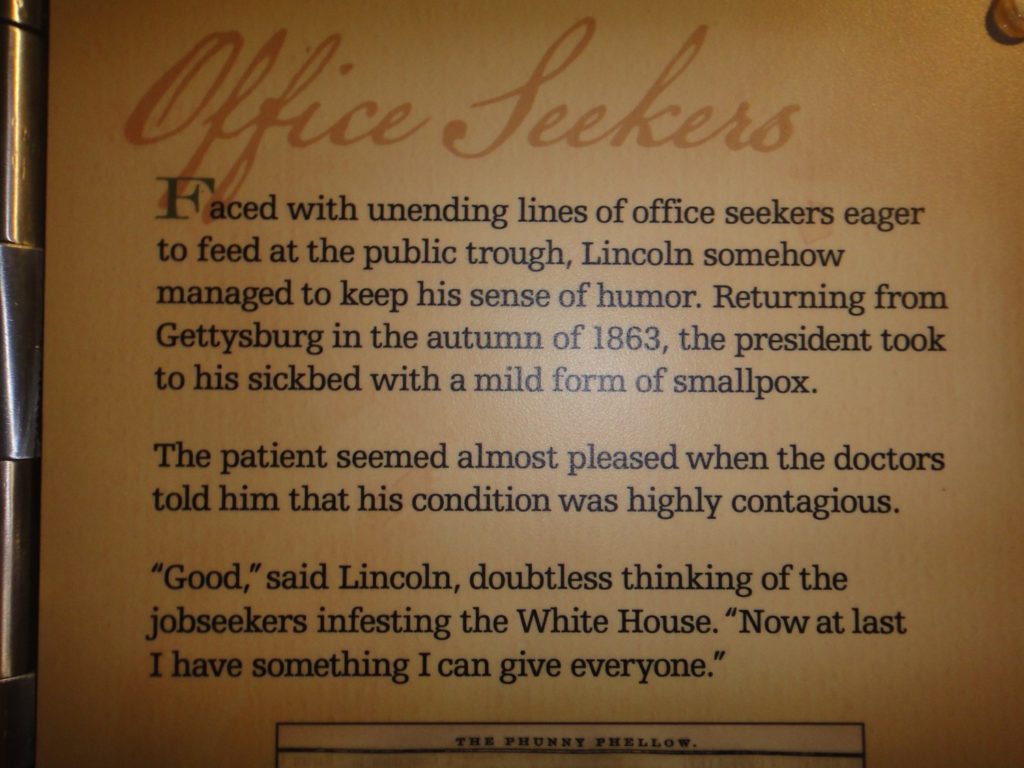

Most people don’t know that Lincoln was feeling ill at the time. It turned out he had contracted smallpox, although not a virulent strain. When I was last at the museum in Ford’s Theater in Washington, DC, I noticed this plaque that I thought was a splendid example of Lincoln’s sense of humor:

The Civil War was a constant strain on Lincoln, yet he learned how to handle the heavy burden placed on him. Evidence is strong that the trials he suffered led him back to Christian faith. The Gettysburg Address and his subsequent Second Inaugural Address give testimony to that faith.