I’m teaching my American Revolution course this semester. Every time I do, I’m impressed with how character shapes history. In this case, the character of George Washington comes to the forefront.

As 1776 drew to a close, it seemed more likely than not that the fledgling nation was in jeopardy and that the Declaration of Independence was destined to be a silly footnote in history, another testament to man’s folly.

Washington’s army, such as it was, composed primarily of untested militia with short-term enlistments, had miraculously escaped the British noose on Long Island in August. Many would comment on the remarkable feat of ferrying the army from that island over to New York City in the dark of night.

Many others would remark with wonder at the almost-supernatural fog that descended on Long Island that morning, thereby allowing the retreat to end successfully. Divine Providence, many would say.

Yet after that, one might wonder where Divine Providence had gone. The ragtag Americans were pushed back in battle after battle, eventually losing the entire island of Manhattan and licking their proverbial wounds for the winter on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River.

Morale in the army and the new nation was at low ebb as Christmas approached. Would the army disintegrate completely? Was this experiment in independence over before it could even begin?

I’ve often taught that history does not revolve around impersonal forces (such as economics). Rather, it’s the individual choices we make that determine what happens next.

Washington took a risk. He knew the mercenary Hessian troops just across the river in Trenton, New Jersey, would be “celebrating” Christmas in their traditional manner—getting stone-cold drunk.

That’s when he made the decision—called rash by some in his ranks—to cross the river in the dead of night and march straight into the Hessian encampment, taking them by surprise.

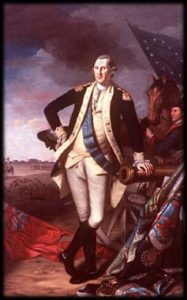

Who hasn’t seen this famous painting? Leaving aside for the moment whether Washington actually stood up in the boat in this heroic pose, he nevertheless was embarking on a desperate and heroic endeavor.

It worked. The surprise was complete. The Hessians surrendered quickly.

British general William Howe was in the area and vowed vengeance for this brazen act. He attempted to surround Washington’s army, but Washington fooled him, again moving his forces during the night while keeping enough camp fires burning to make Howe believe the army was still there.

In the morning, Washington’s troops ran into a contingent of British near Princeton. At first, the troops were timid and started a retreat. Washington himself then rode to the front and rallied them. The result: another stunning victory.

In the morning, Washington’s troops ran into a contingent of British near Princeton. At first, the troops were timid and started a retreat. Washington himself then rode to the front and rallied them. The result: another stunning victory.

When news of these back-to-back military successes found its way into the newspapers, the reeling nation’s morale rose immediately. Washington, by his personal courage and determination, had single-handedly revived their hopes.

Historians, of course, note that this was hardly the end of the trials and that morale would rise and fall throughout the next few years, depending on the circumstances. Washington would face more hard times, even to the point where some in Congress sought to remove him as commander of the army.

Yet this winter of 1776-1777 was crucial to the continuing struggle, a struggle that eventually saw the establishment of America’s independence.

I often call George Washington the indispensable man of this era. This is just one example of why that is true. And I repeat: individual choices, not impersonal forces, are the determiners for how history unfolds.