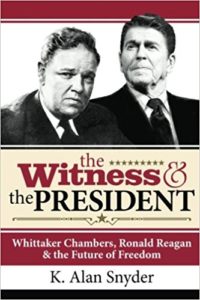

I spent parts of ten years researching the links between Ronald Reagan and Whittaker Chambers. Those years also were spent documenting the difference in outlook between the two conservative icons: Chambers the brooding intellectual who doubted the wisdom of men and their commitment to truth; Reagan the optimist who always saw a bright future ahead.

I spent parts of ten years researching the links between Ronald Reagan and Whittaker Chambers. Those years also were spent documenting the difference in outlook between the two conservative icons: Chambers the brooding intellectual who doubted the wisdom of men and their commitment to truth; Reagan the optimist who always saw a bright future ahead.

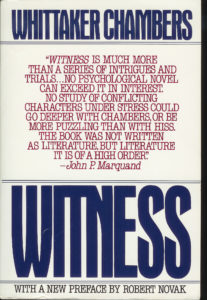

Yet despite that basic disparity in outlook, Reagan was deeply appreciative of what Chambers had taught him, primarily through his autobiography, Witness. Pearls from Chambers’s depth of personal struggle found a prominent place in Reagan’s utterances as president.

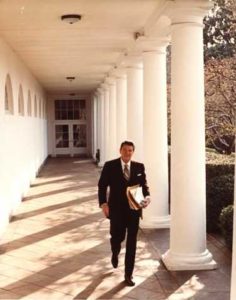

Chambers’s depiction of the communist mentality stayed with Reagan throughout his life. He referred to Chambers a number of times in his speeches. Like all presidents, Reagan had a corps of speechwriters, but he contributed valuable edits to his speeches, adding and deleting lines, passages, and even full pages.

Chambers’s depiction of the communist mentality stayed with Reagan throughout his life. He referred to Chambers a number of times in his speeches. Like all presidents, Reagan had a corps of speechwriters, but he contributed valuable edits to his speeches, adding and deleting lines, passages, and even full pages.

Whenever he included Chambers in a speech, he did not just mention him in passing, but often used direct quotes from Witness. At other times, the author of Witness went unmentioned, yet the words Reagan used sounded familiar to those who knew and appreciated Chambers’s writings.

For instance, at a Fourth of July speech in Decatur, Alabama, in 1984, the president, comparing the totalitarian world of communism with America, said that man was created to be free. “That’s why,” he opined, “it’s been said that democracy is just a political reading of the Bible.” Chambers’s exact words had been, “Political freedom, as the Western world has known it, is only a political reading of the Bible,” but the source for Reagan’s comment is unmistakable. It was a phrase from Witness that found a home in his memory.

Speaking before friendly audiences—those with whom he could share more personally in an ideological sense—the president invoked Chambers regularly. Just two months into his presidency, he addressed the Conservative Political Action Conference Dinner.

In a tone reminiscent of the language used in Witness, he proclaimed, “We’ve heard in our century far too much of the sounds of anguish from those who live under totalitarian rule. We’ve seen too many monuments made not out of marble or stone but out of barbed wire and terror.” He then spoke of “witnesses to the triumph of the human spirit over the mystique of state power,” and declared that “evil is powerless if the good are unafraid,” as if channeling Chambers’s decision to cross over the bridge on his witness and not turn back.

Marxism, he said, is a “vision of man without God” that must be exposed “as an empty and a false faith first proclaimed in the Garden of Eden with whispered words of temptation: ‘Ye shall be as gods.'” Where were all these ideas coming from?

Marxism, he said, is a “vision of man without God” that must be exposed “as an empty and a false faith first proclaimed in the Garden of Eden with whispered words of temptation: ‘Ye shall be as gods.'” Where were all these ideas coming from?

The crisis of the Western world, Whittaker Chambers reminded us, exists to the degree in which it is indifferent to God. “The Western world does not know it,” he said about our struggle, but it already possesses the answer to this problem “but only provided that its faith in God and the freedom He enjoins is as great as communism’s faith in man.”

The real task, Reagan concluded, was a spiritual one: “to reassert our commitment as a nation to a law higher than our own, to renew our spiritual strength.” Only by having this kind of commitment could America’s heritage be preserved. The emphasis on spiritual strength, while also part of Reagan’s core beliefs, certainly was consistent with Chambers’s foundational message.

Near the end of his presidency, in December 1988, addressing his own administration officials, Reagan thought it important to remind them of what Chambers had said. He recalled the sad state of the nation when he took over the reins of the presidency, and how the people had been accused by former president Carter of suffering from the disease of malaise. Everyone at the time, it seemed, had bought into the lie that “there wasn’t much we could do because great historic forces were at work, the problems were all too complicated for solution, fate and history were against us, and America was slipping into an inevitable decline.”

A quote from Chambers seemed appropriate here: “Well, Whittaker Chambers once wrote that, in his words, ‘Human societies, like human beings, live by faith and die when faith dies.’ America, Reagan reminded his audience, possesses “a special faith that has, from our earliest days, guided this sweet and blessed land. It was proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and enshrined in the Constitution.” It was faith in what a free people could accomplish. “And in saying that America has entered an inevitable decline, our leaders of just a decade ago were confessing that, in them, this faith had died.”

A quote from Chambers seemed appropriate here: “Well, Whittaker Chambers once wrote that, in his words, ‘Human societies, like human beings, live by faith and die when faith dies.’ America, Reagan reminded his audience, possesses “a special faith that has, from our earliest days, guided this sweet and blessed land. It was proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and enshrined in the Constitution.” It was faith in what a free people could accomplish. “And in saying that America has entered an inevitable decline, our leaders of just a decade ago were confessing that, in them, this faith had died.”

This particular use of Chambers is instructive: it shows how Reagan almost always took a quote from him and turned it into something positive, no matter how negative the quote was in context. Reagan’s optimism enveloped Chambers’s pessimism and made it encouraging and upbeat instead.

These excerpts from my book are only a small sampling of what awaits the reader who cares to delve into this dual spiritual biography. And a spiritual biography it is, as both men based their beliefs on their grasp of Christian faith.