As I noted in an earlier post, C. S. Lewis didn’t like politics, but he did have strong ideas about what the limits of civil government ought to be. He was interested in proper governing. After WWII, when he saw the Labour government in Britain carrying out its more socialist policies, he was not at all pleased. The national government began to insert itself into everyday life in a manner that Lewis abhorred.

As I noted in an earlier post, C. S. Lewis didn’t like politics, but he did have strong ideas about what the limits of civil government ought to be. He was interested in proper governing. After WWII, when he saw the Labour government in Britain carrying out its more socialist policies, he was not at all pleased. The national government began to insert itself into everyday life in a manner that Lewis abhorred.

In one of his first letters to longtime American correspondent Vera Mathews (Gebbert), he referred to the Labour government as “Mr. Atlee’s Iron Curtain.” Writing to Mathews again two years later, he explained the situation in Britain: “Try living in ‘free’ England for a bit, and you would realize what government interference can mean! And not only interference, but interference in a ‘school marm’ form which is maddening.” He had an example:

For instance, one of our rulers the other day defended rationing, not on the only possible grounds, i.e. the economic, but on the ground that in the old days housewives bought the food which they knew their husbands and families liked: whereas now, thanks to rationing, they are forced to provide their households with a properly balanced diet.

Then he added this quip: “There are times when one feels that a minister or two dangling from a lamp post in Whitehall would be an attraction that would draw a hard worked man up to London!”

Lewis tells Mary Van Deusen, another of his regular correspondents, “Where benevolent planning, armed with political or economic power, can become wicked is when it tramples on people’s rights for the sake of their good.”

This brings to mind Lewis’s famous comment in “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment,” where he warns,

Of all tyrannies a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. . . . Those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.

By 1954, the new Conservative government had ended rationing and Lewis informed his American friends that they didn’t have to send any more food or other supplies to help out. He offered this bit of sarcastic “hopeful” advice to Vera Gebbert: “But cheer up, if our friends the Socialists get back into power, you will be able to exercise your unfailing kindness once more by supplying us, not with little luxuries, but with the necessities of life!” Again to Gebbert, this time in 1959: “We live under the constant threat of a Socialist government, which would finish us off completely.”

To Mrs. Frank Jones, just one week before his death, Lewis sounds the same note: “Our papers at the moment are filled with nothing but politics, a subject in which I cannot take any great interest. My brother tells me gloomily that it is an absolute certainty that we shall have a Labour government within a few months, with all the regimentation, austerity, and meddling which they so enjoy.”

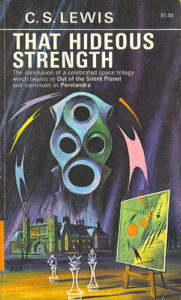

Lewis’s 1958 essay, “Is Progress Possible? Willing Slaves of the Welfare State,” may be his final formal denunciation of the omnicompetent state. In it, he reiterates his earlier warnings from The Abolition of Man and That Hideous Strength.

Lewis’s 1958 essay, “Is Progress Possible? Willing Slaves of the Welfare State,” may be his final formal denunciation of the omnicompetent state. In it, he reiterates his earlier warnings from The Abolition of Man and That Hideous Strength.

If society can mend, remake, and unmake men at its pleasure, its pleasure may, of course, be humane or homicidal. The difference is important. But, either way, rulers have become owners.

He complains that two wars led to “vast curtailments of liberty” and that his fellow countrymen “have grown, though grumblingly, accustomed to our chains.”

Government, he notes, has now taken over “many spheres of activity once left to choice or chance.” Natural law, the rights of man, and the inherent value of the individual, he asserts, have died.

The modern State exists not to protect our rights but to do us good or make us good—anyway, to do something to us or to make us something. . . . We are less their subjects than their wards, pupils, or domestic animals. There is nothing left of which we can say to them, “Mind your own business.” Our whole lives are their business.

Then he offers this poignant commentary:

Again, the new oligarchy must more and more base its claim to plan us on its claim to knowledge. If we are to be mothered, mother must know best. This means they must increasingly rely on the advice of scientists, till in the end the politicians proper become merely the scientists’ puppets. Technocracy is the form to which a planned society must tend.

So, while Lewis avoided public displays of political affiliation, one is on solid ground to say that he was not a fan of nanny government.