“I read all the right books, so I am cultured.” Those of us who seek to expand our knowledge of what might be considered the best of writing over the centuries need to be careful, says C. S. Lewis.

While someone who is drawn to the common conception of culture is certainly better off than one who simply seeks status as one of the in-the-know literati, there is a difference between those who truly enjoy reading and those who do it merely to improve oneself.

The problem, Lewis reveals, is that someone in the latter category

is more likely to stick too exclusively to the “established authors” of all periods and nations, “the best that has been thought and said in the world.” He makes few experiments and has few favourites. Yet this worthy man may be, in the sense I am concerned with, no true lover of literature at all.

Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly, Lewis decried the educational development that made English literature a subject in the schools. Why would a professor of English literature have a problem with that?

“One sad result,” he laments, “is that the reading of great authors is, from early years, stamped upon the minds of conscientious and submissive young people as something meritorious.”

Wait a minute. Don’t we want these young people to consider certain literature as meritorious? Lewis goes on to explain what he has seen happen:

Wait a minute. Don’t we want these young people to consider certain literature as meritorious? Lewis goes on to explain what he has seen happen:

When the young person in question is an agnostic whose ancestors were Puritans, you get a very regrettable state of mind. The Puritan conscience works on without the Puritan theology—like millstones grinding nothing; like digestive juices working on an empty stomach and producing ulcers.

The unhappy youth applies to literature all the scruples, the rigorism, the self-examination, the distrust of pleasure, which his forebears applied to the spiritual life; and perhaps soon all the intolerance and self-righteousness.

This creates, according to Lewis, the wrong kind of seriousness in reading. “The true reader reads every work seriously in the sense that he reads it whole-heartedly, makes himself as receptive as he can.” That means he always reads in the spirit of the writer he is reading, which can often be comical.

“This is where the literary Puritans may fail most lamentably. They are too serious as men to be seriously receptive as readers,” Lewis sadly concludes. “Solemn men, but not serious readers; they have not fairly and squarely laid their minds open, without preconception, to the works they read.”

“This is where the literary Puritans may fail most lamentably. They are too serious as men to be seriously receptive as readers,” Lewis sadly concludes. “Solemn men, but not serious readers; they have not fairly and squarely laid their minds open, without preconception, to the works they read.”

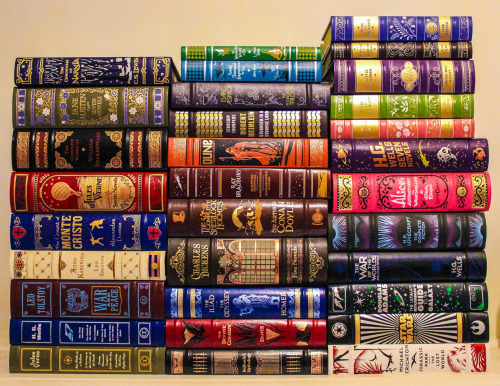

I see the temptation here. My own public education gave me little in the way of the great literature of the past. Now I’m trying to catch up, so to speak. The temptation is to take this route of catching up too seriously: I must dive into all those books that I have neglected over the years; I must know about them so I will be properly cultured.

At least, that’s the pull. So I appreciate Lewis’s warning. I can’t make up for all those other years in the few I may have left. But I can enjoy whatever does come my way and whatever I have the time to read.

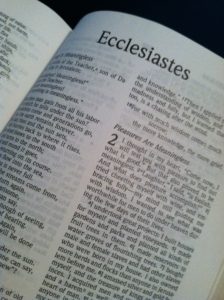

The Biblical grounding I’ve received most of my life is more important than what is deemed the “great literature.” Knowledge of the Bible and the relationship with the Lord that has developed in my 66 years provides me with the foundation for evaluating everything else.

So I can relax on the literary front. As the book of Ecclesiastes reminds us,

So I can relax on the literary front. As the book of Ecclesiastes reminds us,

Of making many books there is no end, and much study wearies the body.

Now all has been heard; here is the conclusion of the matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is the duty of all mankind.

For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil.

That should be my primary focus.