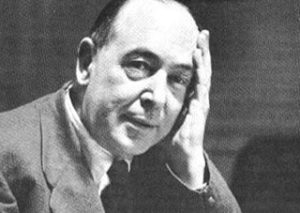

When C. S. Lewis moved from Oxford University to Cambridge University after nearly three decades at Oxford, it was a major event. Oxford never really appreciated what it had in Lewis, whereas Cambridge created a special Chair designed for him.

When C. S. Lewis moved from Oxford University to Cambridge University after nearly three decades at Oxford, it was a major event. Oxford never really appreciated what it had in Lewis, whereas Cambridge created a special Chair designed for him.

His inaugural lecture at Cambridge was a major event as well. In it, he outlined how Europe had become post-Christian, which was a fairly accurate description of Oxford. Lewis noted that nearly everyone thought the switch from pre-Christian to Christian was irreversible. Not so, he explained:

The un-christening of Europe in our time is not quite complete; neither was her christening in the Dark Ages. But roughly speaking we may say that whereas all history was for our ancestors divided into two periods, the pre-Christian and the Christian, and two only, for us it falls into three—the pre-Christian, the Christian, and what may reasonably be called the post-Christian.

This surely must make a momentous difference. . . . It appears to me that the second change is even more radical than the first.

Christians and Pagans had much more in common with each other than either has with a post-Christian. The gap between those who worship different gods is not so wide as that between those who worship and those who do not.

It was in that same lecture that he famously referred to himself as a dinosaur, and that since not many dinosaurs existed anymore, the world should learn from them while they are still around.

Joy Gresham, who would of course become his wife a couple of years later, was present at the lecture. She had a rather whimsical reaction to it, writing in a letter, “How that man loves being in a minority, even a lost-cause minority! Athanasius contra mundum, or Don Quixote against the windmills. . . . I sometimes wonder what he would do if Christianity really did triumph everywhere; I suppose he would have to invent a new heresy.”

Yet, as I survey the Western world sixty years after that inaugural lecture, I have to say that Lewis, as usual, was delivering truth.