An interesting question was posed to me yesterday by a former student, wanting to know what Whittaker Chambers might think of Donald Trump. I gave him my short answer but then decided it would be perhaps insightful to provide a fuller one here today.

For those of you unfamiliar with Chambers, here’s a short synopsis of his life.

Whittaker Chambers, in the 1920s, became a member of the Communist party because he saw it as the hope of a world filled with destruction after WWI. At one point, he was ushered into the communist underground movement where he helped place communists in government positions to influence policy; he also served as a liaison between those officials and underground leaders, to whom he passed on information stolen from the government.

Whittaker Chambers, in the 1920s, became a member of the Communist party because he saw it as the hope of a world filled with destruction after WWI. At one point, he was ushered into the communist underground movement where he helped place communists in government positions to influence policy; he also served as a liaison between those officials and underground leaders, to whom he passed on information stolen from the government.

He soured on communism in the late 1930s as he saw the fruit of Stalinism: the purges of faithful party members, in particular. He had to go into hiding to protect his family, emerging later as a writer for Time magazine, eventually becoming one of its senior editors.

After WWII, Chambers appeared before a congressional committee and told all he knew about the underground subversion taking place. One of the men he fingered in the underground was Alger Hiss, a top State Dept. official. When Hiss denied the accusation, it became front-page news.

To shorten the story considerably, all I’ll say is that Chambers was proven correct, Hiss went to prison, and Chambers then wrote a masterful autobiography entitled Witness, which came out in 1952. It is one of my all-time favorite books.

Sen. Joe McCarthy is infamous for trying to root out the communist conspiracy in the early 1950s. Nothing wrong with that, except McCarthy seems to have been motivated more by personal glory than principle. He also was not a man of towering intellect like Chambers. Neither did he have the inside knowledge Chambers did.

Sen. Joe McCarthy is infamous for trying to root out the communist conspiracy in the early 1950s. Nothing wrong with that, except McCarthy seems to have been motivated more by personal glory than principle. He also was not a man of towering intellect like Chambers. Neither did he have the inside knowledge Chambers did.

Naturally, McCarthy sought to have Chambers on his side publicly. Yet Chambers declined to join in his crusade. Why? It had to do with the character of the man.

In letters Chambers wrote to William F. Buckley, the dean of the modern conservative movement in America, he laid out his concerns—even fears—of what McCarthy might do inadvertently to undermine genuine anti-communism.

In one of those letters, responding to Buckley’s queries as to why he wouldn’t come out in support of McCarthy, Chambers replied,

In one of those letters, responding to Buckley’s queries as to why he wouldn’t come out in support of McCarthy, Chambers replied,

One way whereby I can most easily help Communism is to associate myself publicly with Senator McCarthy; to give the enemy even a minor pretext for confusing the Hiss Case with his activities, and rolling it all in a snarl with which to baffle, bedevil, and divide opinion.

That is why I told Senator McCarthy, when he asked me to keynote his last Wisconsin campaign, that we were fighting in the same war, but in wholly different battles, and that the nature of the struggle at this time enjoins that we should not wage war together.

I do not think that the Senator really grasps this necessity. For it is more and more my reluctant opinion that he is a tactician, rather than a strategist; that he continually, by reflex rather than calculation, sacrifices the long view for the short pull.

While Chambers obviously wanted much of what McCarthy wanted—the exposure of the communist threat—he didn’t see McCarthy as the man to accomplish this.

In that same letter to Buckley, Chambers expressed his deepest fear:

All of us, to one degree or another, have slowly come to question his judgment and to fear acutely that his flair for the sensational, his inaccuracies and distortions, his tendency to sacrifice the greater objective for the momentary effect, will lead him and us into trouble.

In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that we live in terror that Senator McCarthy will one day make some irreparable blunder which will play directly into the hands of our common enemy and discredit the whole anti-Communist effort for a long while to come.

Chambers was prophetic. That’s precisely what happened. McCarthy ultimately went too far with his accusations and fell from his lofty perch politically. Ever since then, anytime a conservative sounds a warning about socialism/communism, critics on the Left have been able to sound the alarm of “McCarthyism.” The senator dealt a deadly blow to intelligent concerns about subversion.

So what about Trump? What would Chambers think if he were here today? Of course, we are dealing with a hypothetical, but we do have Chambers’s own words and feelings about someone who could be disastrous to a good cause. That’s how I see Trump.

Looking again at Chambers’s comments, I can see Trump in many ways. Just as McCarthy was not a principled person, but rather someone out for his own notoriety, so is Trump, in my view. He has no solid principles; he is no conservative; he has little knowledge of constitutional government.

Then there are the tactics. Chambers criticized McCarthy for being merely a tactician, not a strategist, someone who went for the short-term advantage rather than having a long-term goal. Trump again.

Chambers questioned McCarthy’s judgment, his flair for the sensational, and the inaccuracies and distortions in his comments. I see Trump there as well.

Finally, there was Chambers’s biggest fear, that McCarthy would do more damage to the cause in the long run and discredit real anti-communism that knew what it was talking about. I believe Trump will cause great damage to conservatism in our day. People will associate him with that ideology, despite the fact that he is a man of no particular ideology himself. He is merely a narcissist looking for a way to advance himself.

If Trump doesn’t change (and that’s highly unlikely), and he wins the presidency, we may, in the future, hear the alarm of “Trumpism” just as readily as the Left has used “McCarthyism” for the last six decades.

If Chambers were alive today to see what’s transpiring, there is no way I believe he would be a Trump enthusiast. Rather, he would be on the front lines sounding a proper alarm, fearful that conservatism will be undermined by support for Trump.

As an addendum, Ronald Reagan’s son, Michael, has stated that he doesn’t believe his father would have jumped on the Trump train either. From everything I know about Ronald Reagan, I have to agree. Although Reagan called for unity in the Republican ranks, he always wanted that unity to be based on principles.

I find it kind of ironic that those who are excoriating Ted Cruz for not endorsing Trump forget that Reagan, who lost the nomination to Gerald Ford in 1976, spoke at that convention at Ford’s request. While delivering an impromptu speech about the need for Republican principles to win in the election, Reagan pointedly didn’t specifically endorse Ford in that speech. Neither did he campaign for him prior to the election. If that was acceptable for Reagan, why not for Cruz, who has even far more reason to decline a Trump endorsement?

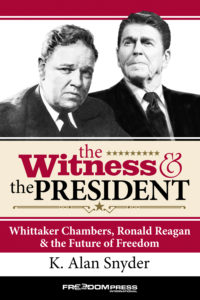

I have studied both Reagan and Chambers for many years. That’s why I came out with this book last year, The Witness and the President: Whittaker Chambers, Ronald Reagan, and the Future of Freedom.

I have studied both Reagan and Chambers for many years. That’s why I came out with this book last year, The Witness and the President: Whittaker Chambers, Ronald Reagan, and the Future of Freedom.

If you want greater depth of understanding of both men, I heartily endorse this book (for some reason). As you dig into the thinking of both Reagan and Chambers, I hope you will come away with a greater appreciation of those who stand on principle.

I also hope you will also grasp why I have not been able to endorse Donald Trump. I want men (and women) of principle taking the lead. We have to look beyond the short-term “victory” of one election and concentrate instead on the long-term. Christian faith and conservative governance are my guidelines; I don’t want them to be denigrated by the unprincipled antics of politicians today.