My last American history post pointed to the integrity displayed by John Adams as he defended the soldiers indicted for the Boston Massacre in 1770. After that event, an uneasy peace prevailed for three years as the British Parliament ceased its efforts to antagonize its American colonies.

The tax on tea still existed, but colonists found other ways to get their tea. The East India Tea Company, closely connected to the government, was suffering, so, in 1773, the Parliament passed the Tea Act.

The tax on tea still existed, but colonists found other ways to get their tea. The East India Tea Company, closely connected to the government, was suffering, so, in 1773, the Parliament passed the Tea Act.

This act permitted the company’s ships to bypass Britain and bring its tea directly to the colonies. Skipping the middle man made the tea cheaper, but the colonists still opposed the landing of the tea because the hated tax remained. They actually saw it as a deceptive way to get around the issue that this tax had been placed on them without any representation.

Britain counted on the cheaper tea being the wedge that would destroy the protest. It read the temper of the colonies incorrectly. The principle of no taxation without representation was more important to the colonists, so they, at a number of port cities, refused to sell the tea.

In Boston, the civic leaders didn’t even want the tea unloaded on the docks. This proved a problem for the captain of those ships, as he needed to unload the tea and move on to his next shipment.

Massachusetts’s royal governor demanded the tea be unloaded. The city authorities said no. The poor captain had to go back and forth between the governor and the people, seeking a solution.

Finally, the governor declared that if he didn’t unload the tea, his ships would be confiscated. The captain returned to the people who were assembled at the Old South Meeting House church to tell them the bad news. Samuel Adams, in charge of that assembly, then announced that this meeting could do no more; everyone went home.

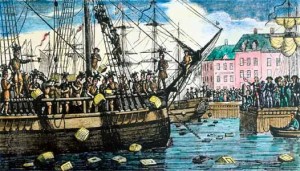

Later, some returned. They were dressed as Indians. They boarded the ships and threw the tea overboard into the harbor. The captain was now free to go on to his next assignment.

Later, some returned. They were dressed as Indians. They boarded the ships and threw the tea overboard into the harbor. The captain was now free to go on to his next assignment.

Accounts of that Boston Tea Party all note that the episode was carried out with no riot; it was a solemn undertaking, a stand for principle. Dressing up as they did probably had to do with helping to disguise those involved. It also was a not-so-subtle sarcastic commentary on the rationale for the tax—protection from the natives.

This action, once it was known, received mixed reactions. Even George Washington wasn’t sure it was a wise move. Benjamin Franklin, over in Britain as a representative for some of the colonies, sought to address the issue of the destroyed private property by talking about compensation.

The British government, however, was in no mood for talking. Massachusetts was going to have to pay for this affront to the King and Parliament.

Was the Boston Tea Party a wise action? It brought the tension between the colonies and the Mother Country to a head. It was the destruction of private property. Yet it also was a stand on principle. The participants believed that if they gave in on this one point, they would be giving in on everything. Once you allow the camel’s nose into the tent—as an old saying goes—the whole camel will want to come in.

It’s a tough call for the historian who is concerned about propriety. Yet there is no debate that what the British did in response to the Boston Tea Party was the direct instigation of hostilities. I will cover that in my next American history post.