When the American colonists protested the Stamp Act in 1765, some did turn to violence over it, but the real political leaders at the time made use of the legal means available to them, offering a petition for a redress of their grievances.

When the American colonists protested the Stamp Act in 1765, some did turn to violence over it, but the real political leaders at the time made use of the legal means available to them, offering a petition for a redress of their grievances.

In a show of colonial unity that was scarce for the day, since each colony usually considered itself more tied to the Mother Country than the other colonies, they came together in a congress in Philadelphia and hammered out what we now call the Stamp Act Resolutions.

Those resolutions stated,

- The colonies were devoted to the British government and considered it the best in the world;

- The rights of the colonists were the same as the rights of all Englishmen;

- Taxes should be imposed only by the consent of the people being taxed, through their own representatives;

- Trial by jury is an inherent and valuable right that should not be curtailed;

- The Stamp Act has a tendency to subvert the rights and liberties of the colonies;

- It ought to be repealed.

If you read this document, you can’t help but come away impressed with the respect and deference shown to the British authorities, particularly the king. This is no call for revolution; it was an appeal they could lawfully forward to the crown.

As it turned out, threats of a boycott of British goods led to a demand from merchants in Britain to repeal the act. Members of Parliament, listening to their own constituencies—not to the reasonable request of the Stamp Act Congress—decided it was in the best interest of their retention of a seat in that legislative body to do what their constituents wanted.

In America, when news of the repeal was announced, there was rejoicing everywhere. Banquets were arranged and toasts offered in honor of the king and his wise government.

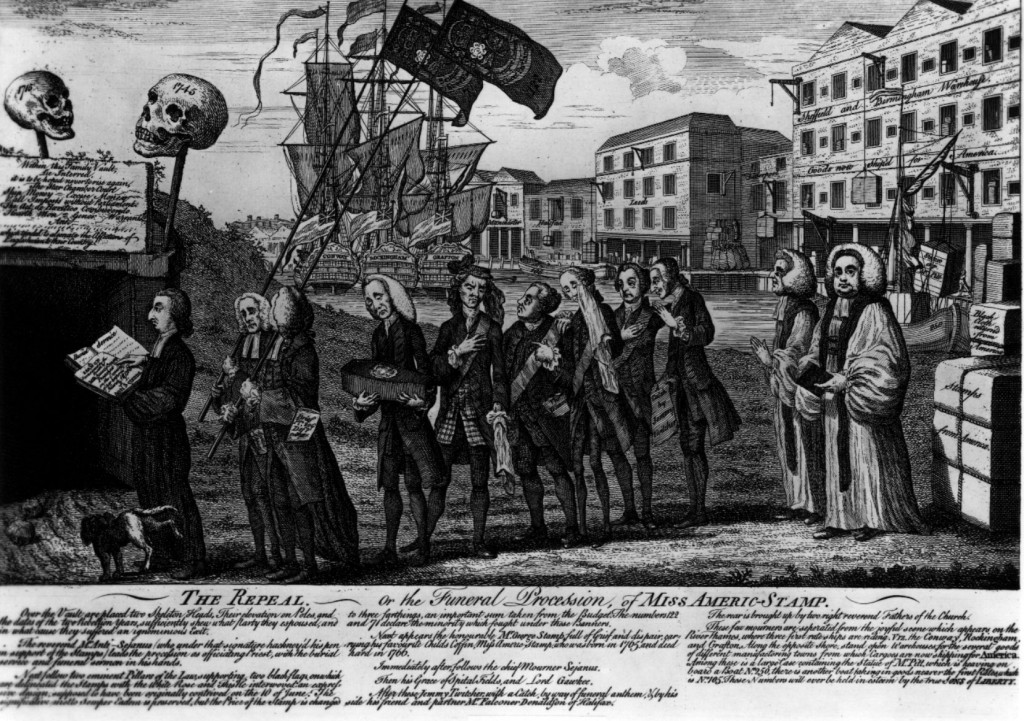

This contemporary cartoon depicts a funeral procession as the Stamp Act was now dead and on its way to be buried once and for all.

The colonists thought the problem was behind them, but at the same time as that act was repealed, Parliament passed another one called the Declaratory Act. There was no tax associated with it, but the declaration contained within it revealed the great divide in viewpoint on the Parliament’s authority. Here are the exact words of this act:

Parliament has full power and authority to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to bind the colonies and people of America, subjects of the crown of Great Britain, in all cases whatsoever. . . .

That all resolutions, votes, orders, and proceedings, in any of the said colonies or plantations, whereby the power and authority of the Parliament of Great Britain to make laws and statutes as aforesaid is denied, or drawn into question, are, and are hereby declared to be, utterly null and void to all intents and purposes whatsoever.

In other words, the colonies had no reason to rejoice. On the matter of principle, the Parliament disagreed with the right of the colonies to tax themselves, and it didn’t care that no colony had a representative in Parliament. In effect, this act said, “We can do what we want, and your only recourse is to obey.”

The problem was not solved at all. Another attempt to tax the colonies came the very next year. That will be the subject of my next installment of American history from a Biblical perspective.