I’ve been reading evangelist Winkie Pratney’s book The Thomas Factor: Dealing with Doubt. Although it’s not necessarily intended as a devotional book, that’s the spirit in which I’m reading it, and so many of his comments and explanations have served to confirm what I already know and have challenged me to remain committed to the Truth.

I’ve been reading evangelist Winkie Pratney’s book The Thomas Factor: Dealing with Doubt. Although it’s not necessarily intended as a devotional book, that’s the spirit in which I’m reading it, and so many of his comments and explanations have served to confirm what I already know and have challenged me to remain committed to the Truth.

I was particularly impressed with his treatment of what it means to have deep conviction of belief. Here’s a sample:

We are to take truth and personal convictions seriously. How do you know if you really have convictions? . . . No conviction is truly your own unless you’re prepared to hold it even if all others are against it. I’ve sometimes told young Christians, “You need to follow Jesus even if everyone you know who is supposed to be a Christian turns his back on both Him and you.”

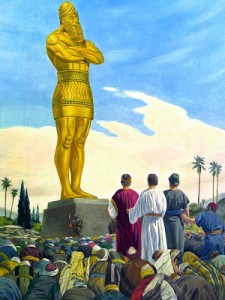

Pratney then expounds on the well-known Biblical example of the three Hebrews who refused to bow down to the statute of King Nebuchadnezzar. They stood out like the proverbial sore thumbs while everyone else bowed. Nebuchadnezzar was irate and gave them one more chance: either bow down or go into the fiery furnace. Pratney then invites us to be one of those three and think about how we might have rationalized our disobedience to God:

Pratney then expounds on the well-known Biblical example of the three Hebrews who refused to bow down to the statute of King Nebuchadnezzar. They stood out like the proverbial sore thumbs while everyone else bowed. Nebuchadnezzar was irate and gave them one more chance: either bow down or go into the fiery furnace. Pratney then invites us to be one of those three and think about how we might have rationalized our disobedience to God:

What would you do? Would you smile and, so as not to offend, go ahead? Would you bow (certainly not enthusiastically) and mutter to yourself: “Well, God knows I am not really bowing ‘in my heart.’ After all, He has gone to all this trouble to put me in a place of some leadership and influence with these ungodly pagans and He certainly wouldn’t want all that to come to an end now because of some silly little external show. I’ll bow (outwardly only, of course) just to please the king, but God knows that it is all only an outward appearance. In my heart of hearts, am I not still following God?”

If those rationalizations sound familiar, they are. They’ve been used time and again throughout history to sidestep real conviction and try to convince oneself that disobedience really isn’t disobedience. The three Hebrews knew what awaited them, yet they stood firm. Pratney continues,

These boys knew who God was. They knew something of His wisdom, His character, and His power. They knew what He could do. They also knew some way or other, in life or by death, they would shortly be out of the king’s power. They knew God could intervene. But they did not know, for them, for then, if God would. And knowing the king as they did, knowing that he would do exactly as he said, knowing fully the consequences of a polite but firm refusal, they refused anyway. “But if not, we will not bow down.”

That’s conviction. It has to do with commitment—even if you don’t understand the whole thing, even if you don’t know what’s going on , even if you don’t know what is going to happen to you.

In our day, with the culture rapidly slipping away from even tolerating Biblical convictions, will we stand firm? If we rationalize our disobedience, it doesn’t change the fact that it is disobedience. The Lord is looking at each heart, seeking those who will remain faithful under trial.