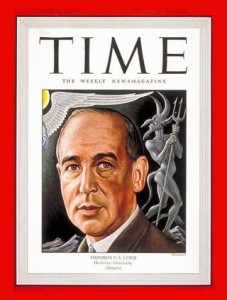

Fifty years ago yesterday, C. S. Lewis, just one week shy of his 65th birthday, slipped into eternity. At the ripe young age of twelve, I was unaware of his death. The whole world was watching the unfolding events surrounding the JFK assassination, so the passing of a university professor whose writings had awakened a generation to the vibrancy of Christianity, went virtually unnoticed.

Fifty years ago yesterday, C. S. Lewis, just one week shy of his 65th birthday, slipped into eternity. At the ripe young age of twelve, I was unaware of his death. The whole world was watching the unfolding events surrounding the JFK assassination, so the passing of a university professor whose writings had awakened a generation to the vibrancy of Christianity, went virtually unnoticed.

Lewis himself felt his influence had waned in his later years. Most observers agreed, and they predicted his works would slip into obscurity with him. Both Lewis and those cultural observers were wrong.

I never read any of Lewis’s works until after I was in college. If I remember correctly, the first time I heard him mentioned was in one of my classes, when I inadvertently overheard a conversation between a couple of students sitting in front of me. One girl seemed quite taken with a book of Lewis’s—either The Screwtape Letters or That Hideous Strength [my memory on that point is fuzzy]—and it piqued my interest. Over the next several years, he became one of my favorite writers, as my own faith grew. He obviously has remained so, since I use Saturdays in this daily commentary to draw attention to some of his most poignant quotes and valuable insights.

Lewis is difficult to classify; he was a Christian writer, to be sure, but he was far more. His first writings were anything but Christian, as he emerged from his early education and his WWI experience a convinced atheist. The transformation to orthodox Christianity was not easy, as he struggled with many intellectual objections. Yet with the help of friends like J. R. R. Tolkien—later famous as author of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings—he found his way “home.”

He began his academic tenure at Oxford as a philosopher and an aspiring poet. His focus later shifted to English literature, where he earned praise as an original thinker and critic. He used all of that background and training as the basis for his specifically Christian writings. His first foray into that realm was philosophical and apologetic. His very first book as a Christian was titled The Pilgrim’s Regress, a reformulated Pilgrim’s Progress that tackled the many philosophical traps modern man falls into.

From there, he ventured into science fiction, with the “Ransom Trilogy”: Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength. Even before completing that series, he gave a series of radio broadcasts on the BBC during WWII that catapulted him into national prominence. Those talks later were edited and bound together as the bestseller Mere Christianity. Simultaneously, his fanciful side more fully emerged with the popular Screwtape Letters, consisting of supposed letters of advice from a senior devil to his junior, instructing him how to lead a man into hell. It has remained one of Lewis’s most admired works, not only for its imaginative approach but also for its practicality as we seek to live the Christian life and avoid the pitfalls Satan places in our path.

From there, he ventured into science fiction, with the “Ransom Trilogy”: Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, and That Hideous Strength. Even before completing that series, he gave a series of radio broadcasts on the BBC during WWII that catapulted him into national prominence. Those talks later were edited and bound together as the bestseller Mere Christianity. Simultaneously, his fanciful side more fully emerged with the popular Screwtape Letters, consisting of supposed letters of advice from a senior devil to his junior, instructing him how to lead a man into hell. It has remained one of Lewis’s most admired works, not only for its imaginative approach but also for its practicality as we seek to live the Christian life and avoid the pitfalls Satan places in our path.

One of my personal favorites is a slim volume, The Great Divorce, which explores what it might be like if a busload of hell-dwellers had the opportunity to go to heaven for one day. How might they respond? I’ve never read a more insightful peek into the utter selfishness of man than what I find in this book. Try it; you might like it.

His The Abolition of Man is a magnificent treatise on the absurdity of moral relativism and nihilism. It’s been quite a while since I’ve read that one; I need to get back to it soon. That’s one way to know the value of an author. If you feel compelled to reread, you know you have found a treasure.

One of my favorite Lewis pieces is a sermon he gave called “The Weight of Glory.” His description of how common everyday people should be viewed instead as potential heavenly creatures or potential horrors one would meet only in a nightmare is striking. It makes you see everyone in a distinct, eternal light.

Lewis’s breadth of scope in his works is highlighted of course by The Chronicles of Narnia. They are ostensibly children’s books—and they are—but their appeal extends to adults who want to ensure their own children are immersed in them. The lessons within those books are for all ages, and although the writing style is superb for children, it doesn’t insult the intelligence of their elders. One comes away from those books, particularly, for me, The Last Battle, with a clearer understanding of the temporal nature of our current world and an anticipation for the arrival of the next one, which will be better by far.

I’ve hardly exhausted what could be said about Lewis’s works, both the ones noted above and others. His influence continues. His home nation of Great Britain has been slow to recognize his worth; America seems to have understood and appreciated him more over the decades. Oxford never fully grasped his genius, never promoted him, and many of his supposed colleagues despised him because of his popularity and his disdain for academic politics. Yesterday, though, he finally received his due, in part. He is now honored at Westminster Cathedral with a special tribute in its famed Poets Corner.

If you haven’t delved into the writings of C. S. Lewis yet, I urge you to do so. If you’re an afficianado of his labors as I am, perhaps it’s time to reread something you haven’t read for some time. He was a man used by God during his life, and even more so since his death. Of course, he lives on still. Read The Last Battle and “The Weight of Glory” to help grasp that truth more clearly than ever.