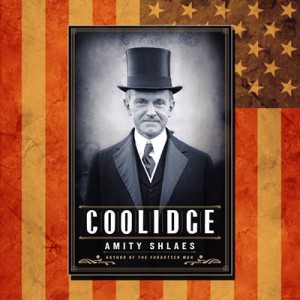

A few weeks ago, I gave an endorsement to Amity Shlaes’s biography of Calvin Coolidge, even though I had only read half the book at that time. I’ve now completed it, and my endorsement not only holds but is greater than before. She presents Coolidge from all angles, inspecting both strengths and weaknesses, triumphs and disappointments.

A few weeks ago, I gave an endorsement to Amity Shlaes’s biography of Calvin Coolidge, even though I had only read half the book at that time. I’ve now completed it, and my endorsement not only holds but is greater than before. She presents Coolidge from all angles, inspecting both strengths and weaknesses, triumphs and disappointments.

Along the way, she gives many insights into the character of the man himself. He took office as president upon the death of Warren Harding. While waiting to make the White House his home, he was staying at the Willard Hotel in Washington. One incident during that interregnum showcases not only Coolidge’s character, but also how different security was for a president in the 1920s. Shlaes recounts,

One early morning in the Willard bedroom, a sound woke Coolidge. A strange young man had broken in and was going through his clothing. In the morning light, Coolidge could see that the burglar had taken a wallet, a chain, and a charm. “I wish you wouldn’t take that,” Coolidge said. “I don’t mean the watch and chain, only the charm. Read what is engraved on the back of it.” The burglar read the back: “Presented to Calvin Coolidge . . . by the Massachusetts General Court.”—and stopped in dead shock. He was robbing the president. It emerged that the burglar was a hotel guest who had found himself short of cash to return home. Coolidge gave the burglar $32, what he called a “loan,” and helped him to navigate around the Secret Service as he departed.

I love that story, hard as it is to believe it could actually have happened. Certainly nowadays it couldn’t. But it reveals a soft side to Coolidge and a willingness to reach out to someone in need, even someone who was in the process of robbing him.

Tragedy hit the Coolidge family about a year after he ascended to the presidency. His son, Calvin Jr., died suddenly from a blister he had gotten from playing tennis. It was a bewildering episode, since no one suspected a blister could lead to death. The Coolidges were devastated. Yet God uses the trials in our lives to get our attention. As Shlaes relates,

Protecting the space that faith enjoyed in American culture, the realm of the spiritual, seemed to him [Coolidge] especially important. In those early days after Calvin’s death he had refused many appointments, but had agreed to talk to a group of Boy Scouts in a telephone hookup. “It is hard to see how a great man can be an atheist,” Coolidge had told the boys. “We need to feel that behind us is intelligence and love.” Now he was preparing a speech for the dedication of a statue of a Methodist bishop, Francis Asbury. In that speech he wanted to make clear his conviction that government’s power, since the days of Jonathan Edwards, had derived from religion, and not the other way around.

Those are just two snippets from the book. It abounds with others. I highly recommend it.