Those who know me know I’m convinced America’s roots are fundamentally Biblical. I deplore efforts to wipe out Biblical influence in the Founding of this country. However, I also deplore any effort to force a Christian interpretation on certain events or individuals. We must be honest with the evidence.

The drive to reestablish the basis for our Biblical roots, at least in more popular Christian reading, probably began with Peter Marshall’s The Light and the Glory, which appeared in the 1970s. I read it at the time and was impressed, although I also was slightly disturbed by how the author concocted conversations between historical figures. Literary license, I guessed. Since then, many have entered the field, trying to augment what Marshall began.

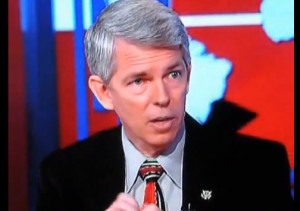

The most successful writer in this genre has been David Barton. I’ve read a number of his books and have appreciated the fact that he has tried to unearth documentation that others might have missed. In fact, I was pleased when he admitted that one supposed James Madison quote everybody was using to show that the Founders based our government on the Ten Commandments was, in fact, spurious. That displayed honesty, and I always seek that in someone who names the name of Christ. We must be honest above all.

The most successful writer in this genre has been David Barton. I’ve read a number of his books and have appreciated the fact that he has tried to unearth documentation that others might have missed. In fact, I was pleased when he admitted that one supposed James Madison quote everybody was using to show that the Founders based our government on the Ten Commandments was, in fact, spurious. That displayed honesty, and I always seek that in someone who names the name of Christ. We must be honest above all.

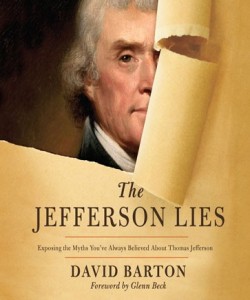

Barton’s latest book, The Jefferson Lies, was published by Thomas Nelson, a respected Christian publishing house. I admit I haven’t yet read the book, but that’s going to be a moot point very soon. Thomas Nelson has ceased its publication and pulled it from the market. Is this a case of pressure from the historical profession, which is so secular it doesn’t want to give Barton’s views a chance to be heard? If so, why are conservative Christian historians critiquing it? Have they gone over to the dark side?

Barton’s latest book, The Jefferson Lies, was published by Thomas Nelson, a respected Christian publishing house. I admit I haven’t yet read the book, but that’s going to be a moot point very soon. Thomas Nelson has ceased its publication and pulled it from the market. Is this a case of pressure from the historical profession, which is so secular it doesn’t want to give Barton’s views a chance to be heard? If so, why are conservative Christian historians critiquing it? Have they gone over to the dark side?

One of the goals of the book is to establish Jefferson as a Founder who didn’t really abandon Christian orthodoxy, among other presumed lies about the third president. There’s only one problem with that: Jefferson did indeed desert orthodox Christianity and considered it a superstition. All one has to do is read many of his letters to John Adams, another of the Founders who fell away from the faith. In one of my earlier blog postings, I pointed specifically to a letter Jefferson wrote to Benjamin Rush, a fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, in which he stated he was a Christian, but only in the sense that he was following a Jesus who never claimed to be anything other than a man. In other words, Jefferson admired Jesus’ moral teachings, but didn’t consider him to be God.

Then there’s Jefferson’s Bible. Yes, it was meant to be used to help spread civilization to the Indians, but it was never, in Jefferson’s mind, to be used to convert them to orthodox Christianity. He really did reject the miraculous in the gospels, declaring them to be later insertions by Christians who wanted to make Jesus into more than He really was. That’s why he omitted miracles—even Jesus’ resurrection— in his version of the gospels. There’s just no getting around those facts. They are well established by solid research, and as a Christian, I have to accept their validity.

I certainly don’t mean to speak ill of Barton. I can sympathize with his desire to highlight the role of Christian faith in our Founding. But we do the Christian faith a disservice when we go beyond what the evidence reveals, thereby undermining whatever good we may do otherwise.

Are there historians who denigrate Christianity’s influence in our formative years? Absolutely. Some will ignore vital evidence that points to that influence. Yet the antidote is not to commit the same error on the other side. While I don’t think a non-professional historian like Barton should be dismissed simply because he hasn’t jumped through all the hoops to earn a doctorate, nevertheless, some of those hoops are valuable. I’m glad I had to learn research methods and read widely on the various eras of American history. That training, in itself, is not secular; it all depends on how it is used.

I’ve taught American history now for more than twenty years. When I teach my introductory course that focuses on America from its colonial beginnings to the aftereffects of the Civil War, I begin by showing students that different schools of historical interpretation exist. I take them through a school of thought that believes all the good of America’s Founding came from the Enlightenment’s embrace of human reason. Historians from that school summarily dismiss the Pilgrims as a group hardly worth mentioning and portray the Puritans as harmful for their autocratic ways and doctrinal dogmas.

After that, I tell them about those who are so focused on the existence of slavery during this era that they assume the Founders are all hypocrites who offer us nothing valuable as a study. At the opposite extreme, I say, are those who view the Founding as a Golden Era, almost a utopia, where all things were Christian. I then let them know I have issues with all three of those schools of interpretation.

Finally, I present where I’m coming from as I look at American history, particularly its Founding Fathers. I believe it’s important to inform students where a professor stands on major interpretational issues. No one learns in a vacuum. I tell them I see the Founding era as one based on Biblical principles. This means the consensus of the society at that time was Christian, and human laws were based on a Biblical concept that God’s law was supreme and eternal, and that societal laws had to be in accordance with God’s law. Not everything was perfect and/or Christian; neither were all the Founders. Yet there was a general agreement that society functioned best when Biblical values were incorporated into it.

Some Christian historians don’t agree with me. They don’t see the influence of the faith as readily as I do. That’s their prerogative. Yet I must be sure that my arguments for my views are as historically sound as possible. I cannot try to prove that which is demonstrably untrue. I’m afraid David Barton fell into that error this time. I sincerely hope, for his sake and for the sake of accuracy in Christian historiography, that he will reconsider what he is attempting to prove. I want nothing but the best for him personally; that starts with acknowledging he has misstated the historical evidence in this case.

Meanwhile, I genuinely hope that my fellow historians will be just as eager to hold their more secular colleagues accountable for any inaccuracies they espouse. The critique needs to apply equally.